The Point Reyes ranch has been in the family since 1946. After a reluctant settlement deal, the family gathered for a bittersweet reunion and final roundup.

The post Point Reyes Family Says Goodbye to Cherished Ranch After Years of Legal Battles appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

Early dawn on Point Reyes brings another sunrise without a sun, the May fog shrouding this Saturday as winds whip up like they often do out on the peninsula.

“It’s all I’ve ever known,” says rancher Kevin Lunny. He’s talking about the wind, the light, the smell of cows, the scent of salted air off the sea — almost every detail in his life — as he drives a 4×4 into the pasture where his grandfather first set foot in 1946.

An executive at Pope and Talbot in San Francisco, Joe Lunny Sr. was a steamship man, not a farmer. But after buying a run-down dairy on the Historic G Ranch, he learned, often the hard way, from old family ranchers nearby, like the Kehoes and the Mendozas, who had worked the land long before he arrived. His son, Joe Lunny Jr., who was 17 at the time — he’s now 94 — remembers, “I came out here as greenhorn as you can be.”

Over these past few weeks, everything Kevin Lunny does, whether closing a pasture gate or fixing a fence wire or taking an evening walk down to Abbotts Lagoon with his wife Nancy — he keeps asking himself, will this be the last time?

Today, at least, one thing appears sure: This is the final cattle roundup at Lunny Ranch. The last time he’ll ever bring cows into corrals and separate them. He’s known this day might arrive sooner than later, for years now.

“But it’s still hard,” he says.

More than a decade ago, when he lost a long-shot bid to renew the federal lease inside Point Reyes National Seashore for his Drakes Bay Oyster Company, he had a premonition this day might come. After the seashore was created in 1962, with provisions for pastoral and wilderness lands, the longtime ranching families were reluctant to sell their land to the federal government, even with agreements to lease the land back.

Over the decades, those agreements came increasingly under fire from environmental groups who want more of the park turned over to wilderness and wildlife. After years of lawsuits and mediation between ranchers, environmental groups, and the National Park Service, which owns the land, the park is effectively shutting down the farm Lunny grew up on, one of a dozen set to close by next year under a voluntary buyout brokered by The Nature Conservancy.

Lunny, a frontman in many of the biggest fights over the seashore in the past decade, doesn’t want to argue over the details anymore. He held out as long as he could. Finally, his father came to him and said, “I think we have to come to a yes. I don’t want to see it kill you.”

In January, he was the last of 12 ranchers to sign the settlement, which includes a reported $30-million payout to the ranchers who agreed to leave the land forever by next spring.

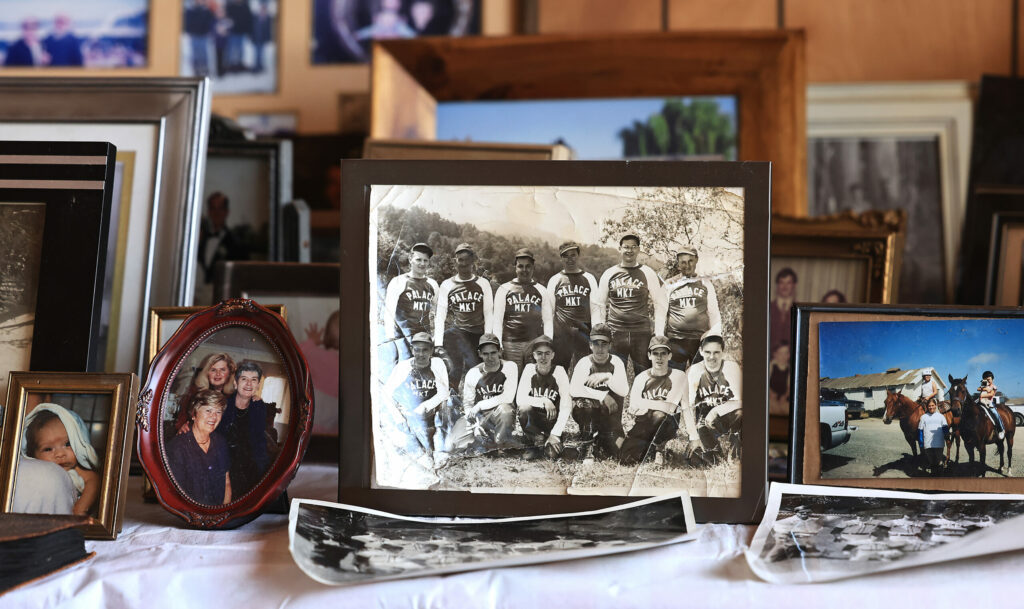

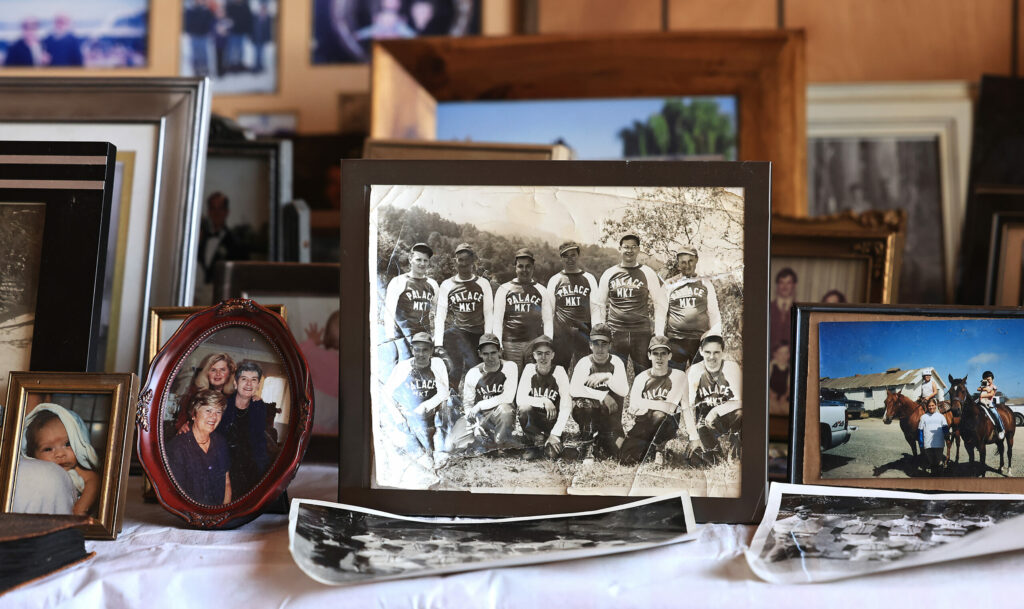

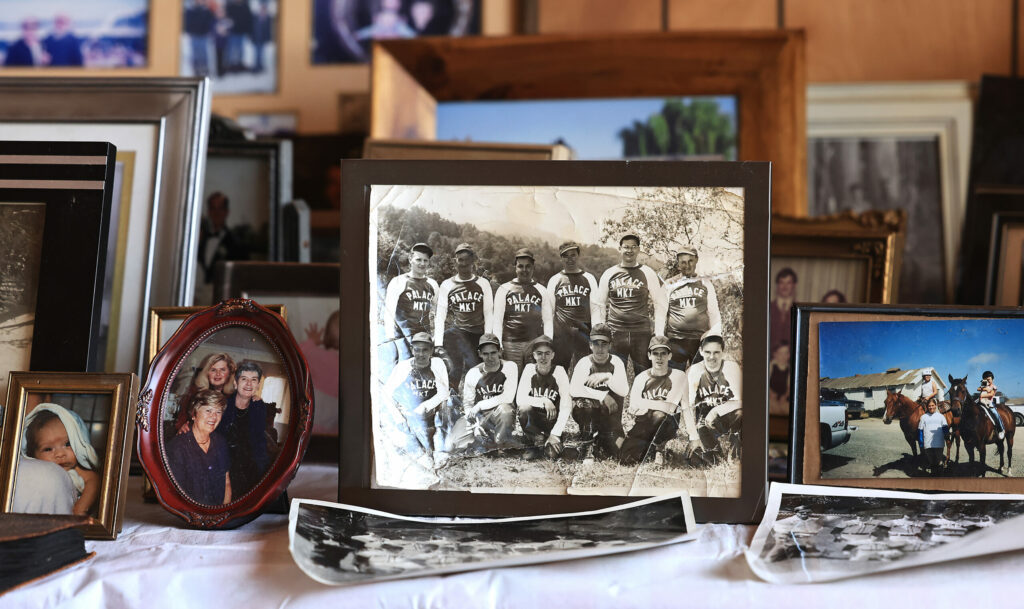

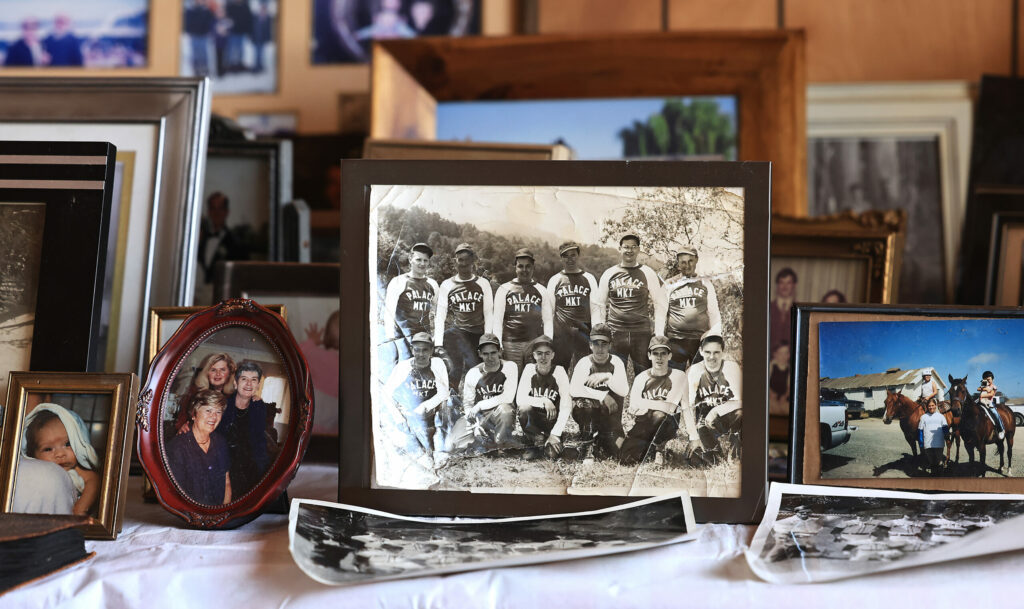

Now, Lunny looks out on the pasture where his grandkids, other family, and old friends make wide sweeps on dirt bikes, horseback, and 4x4s, leading the cattle toward the corrals.

“We’ve never had this many people to gather cows in our life,” he says. “It’s really kind of everybody in the family coming together. It’s very emotional for everybody. It shows you how this place has been meaningful for generations.”

His daughter Brigid Mata, who has worked the farm since she was a child, says she originally thought maybe the last roundup should just be small and super-intimate. “But my dad said, you know, everyone has memories here. Everyone wants to be a part of it.”

On this final roundup, there are 90 mother cows, 30 bred heifers, 85 calves — many that will relocate to a pasture in southern Oregon for now. And 55 2-year-olds going to slaughter.

Over the next few hours, friends and family from as far and wide as Tennessee, Washington and all over California, will lend a hand helping sort cattle while a vet does pregnancy checks on mother cows. Mata will attach new ear tags on the cows going to Oregon, and Nancy Lunny will log every detail from the vet checks in her notebook. Eventually, empty boxes of doughnuts make way for an open-pit barbecue firing up. It feels like a family reunion, with all the hugs and back-slapping and kids running around.

“On the outside we might be laughing and smiling and carrying on, but on the inside, everyone is sad,” says Kevin Lunny.

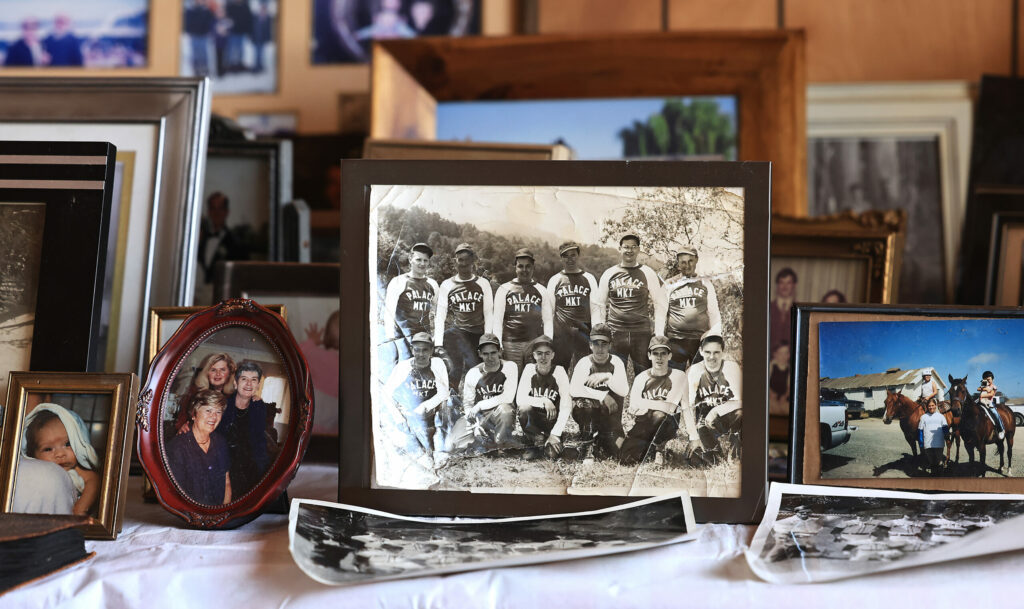

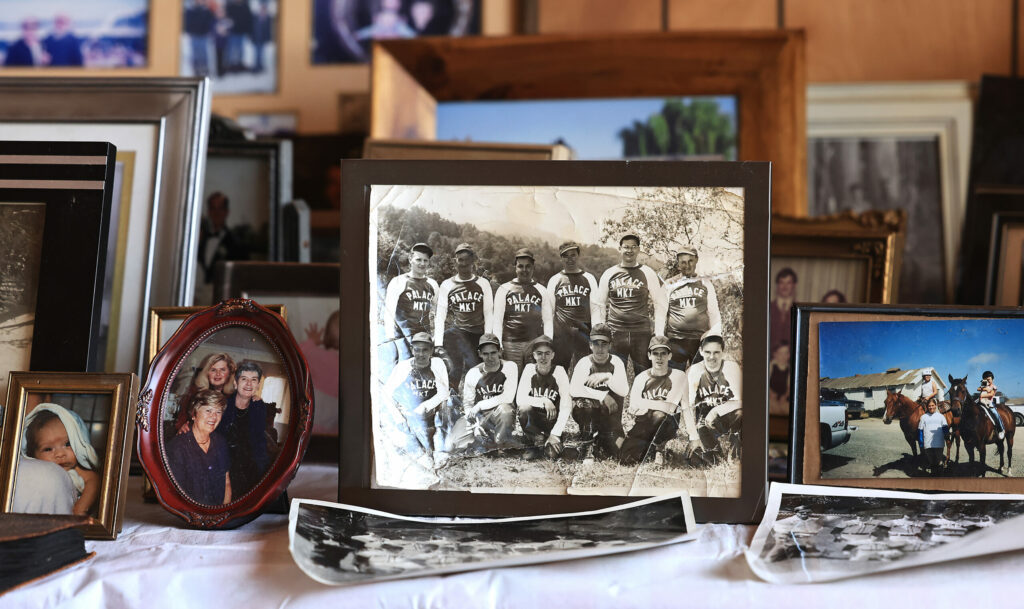

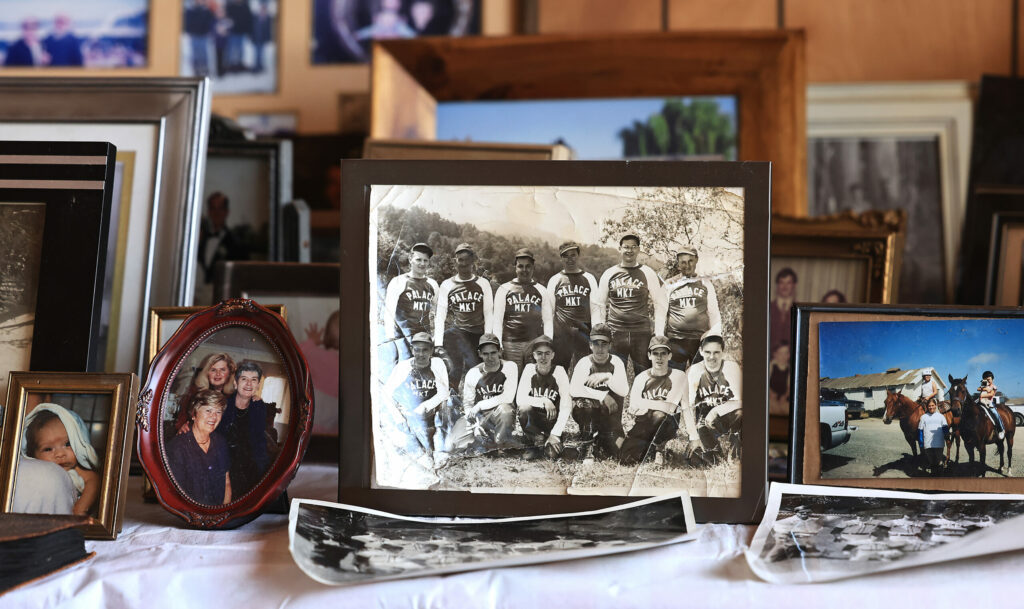

His father, Joe Lunny Jr., is taking it the hardest. He’s watching from afar, on the patio of the main house. As people park and walk up the driveway, they stop to pay their respects as if giving their condolences at a funeral. Joe leads them through a room with walls filled with family photos and deer mounts. Nearby, framed on the wall, an old Press Democrat story headline reads, “Ranching in Paradise.”

Over the years, it became anything but that.

“I thought I would die here one day,” says Joe Lunny Jr., choking back tears as he reaches out to the land with one arm.

Will he ever return to visit?

“Why would I?” he says.

By this time, in the thick of summer, Kevin and Nancy Lunny plan to be settled down in their new home on 10 acres near Auburn. His father will split time with them and his sisters, who live in Penngrove and McCloud near Mt. Shasta.

On the farm outside Auburn, there’s a pond stocked with bass and bluegill that his grandkids love to fish. Kevin Lunny thought he would have a hard time adjusting to such a quiet place, without the constant sound of the ocean and harsh winds he grew up with in Point Reyes. But a creek running through the property “that babbles year-round” has filled any void. He also kept a few cows, because he says it would be hard to live without them, and he has a barn.

Lunny has promised to stay involved in the ongoing battle over ranching in the park and help other ranchers in need. Lately, there have been rumblings that bureaucrats in Washington might reverse the deal that ended ranching in the park. If that happened, would he be interested in coming back to Point Reyes?

“In a heartbeat,” he says. “We’d do it in a second.”

But he already spent the money.

“We signed a contract,” he says. “We committed never to come back.”

The post Point Reyes Family Says Goodbye to Cherished Ranch After Years of Legal Battles appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

Oprah's annual holiday gift guide features favorite products from a Petaluma ranch and a Marin-based cheese company.

The post Sonoma and Marin Products Make Oprah’s 2024 List of ‘Favorite Things’ appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

Oprah Winfrey recently released her hotly-anticipated annual list of “Favorite Things.” Among them is a body butter from Petaluma’s McEvoy Ranch and a cheese from a Point Reyes company.

With over 100 items on her list, Oprah highlights several small businesses with items that make great gifts and stocking stuffers for the holiday season.

McEvoy Ranch Whipped Body Butter, $39

The family-owned McEvoy Ranch, located in rural south Petaluma, produces award-winning olive oils — and now its beauty products are in the national spotlight. Oprah called McEvoy Ranch’s Whipped Body Butter “a rich and luxurious moisturizer.”

The body butter is made with the ranch’s organic extra virgin olive oil — as well as rosehip fruit oil, hyaluronic acid and shea and cocoa butters — for a skin-nourishing, hydrating cream. Scents include citrus, lavender, unscented and an herbaceous verde. The whipped body butter is currently on sale for $39 on McEvoy Ranch’s website.

5935 Red Hill Road, Petaluma, 707-778-2307, mcevoyranch.com

Point Reyes Cheese & Thank You Gift Set, $95

Among Oprah’s favorite food gifts is a cheese gift basket from Marin-based Point Reyes Farmstead Cheese Co. The Cheese & Thank You gift set is filled with a selection of handcrafted cheeses to pair with crackers and a spread.

“Thanks to four artisanal cheeses — TomaRashi, Gouda, Bay Blue and a just-so-good Truffle Brie — sweet olive oil crackers and a sour cherry spread,” Oprah stated, “the lucky recipients of this gift box (created just for us) will use the enclosed cheese knife to dive right in.”

This is the second year in a row Point Reyes Farmstead Cheese Co. landed on Oprah’s coveted favorites list. Last year, Oprah featured the company’s Cheese Celebration Collection.

14700 Highway 1, Point Reyes Station, 800-591-6878, pointreyescheese.com

Past Oprah-approved local products

This isn’t the first time Sonoma County products fell into Oprah’s good graces. In 2016, she selected Guerneville’s Big Bottom Market biscuits among her favorites. The market changed its name to Piknik Town Market last year, following the departure of co-owner Michael Volpatt. New owner Margaret van der Veen confirmed the market still offers the famous biscuits.

In 2021, Santa Rosa-based Sonoma Lavender Co. made it on Oprah’s list for its lineup of scented stuffed animals. The heatable plushies contain a pouch of fragrant, soothing local lavender or eucalyptus.

In Napa Valley, Model Bakery’s English muffins made it on Oprah’s favorites list four times, in 2016, 2017, 2020 and 2021. The Napa County bakery opened a location in the East Bay in 2022.

The post Sonoma and Marin Products Make Oprah’s 2024 List of ‘Favorite Things’ appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

Legendary local cheesemonger Colette Hatch - aka Madame de Fromage - shares some of her favorite artisan cheeses from Sonoma, Marin and beyond.

The post Great Local Cheeses To Try, According to Madame de Fromage appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

Colette Hatch – aka Madame de Fromage – has worked as a cheesemonger at Oliver’s for more than a decade. Click through the gallery for some of her favorite local cheeses.

Madame de Fromage doesn’t take cheese lightly. Literally.

Balancing a large wooden board nearly the size of her petite torso, she’s snatching up wedges of all her favorite local cheeses from the refrigerated cases of Oliver’s Market in Windsor.

Most of us only know her by her nom de guerre, Madame de Fromage. She has worked for Oliver’s for more than a decade as cheesemonger and buyer and knows all the ins and outs of the local cheese trade. She is a tireless champion or opinionated critic of every slice that comes under her experienced nose.

The whole mass of samples is threatening to topple onto the floor as Madame — whose name is Colette Hatch — walks and talks about everything from mascarpone to mozzarella in a fast-paced, thick French accent. With Madame you either keep up or get out of the way.

Undaunted by the pile, she continues pulling cheese, looking for one particular wedge.

“The one with the bloomy rind?” she says to one of her white-coated cheese department staff, sifting through the piles of triple cream brie, Camembert, goat cheese, sheep’s milk cheese, fresh cheese, and aged cheeses. The way Hatch says it sounds more like “zee wan wis zee blumay wind.”

It’s entertaining just to watch Hatch poke deft fingers through the hundreds of varieties and pull out her favorites. We’re about to go on a tasting expedition together, with Hatch explaining some of her current favorites.

“You’ve had this one, of course,” she points to a wedge of Joe Matos St. George cheese, an aged raw cow’s milk cheese that’s been a local favorite since the family set up business in Sonoma County in 1979. It’s a nutty, hard cheese that along with Sonoma’s Vella Jack and Laura Chenel’s goat cheeses set the stage for artisan cheesemakers in the region. It’s also a familiar flavor, so she passes over it and continues the search for more obscure favorites.

In the nearly three decades since Hatch came to Sonoma County, the local cheesemaking scene has leapt into the national consciousness. First there was Chenel, who brought goat cheese to American plates from her Sonoma County dairy in the 1980s. Then came Redwood Hill Goat Cheese, Bellwether Farms, Marin French Cheese, and perhaps one of the largest success stories of all, Cowgirl Creamery — whose Red Hawk and Mt Tam are dairy darlings.

Not to mention the dozens of tiny artisan cheesemakers whose small-batch creations grace dozens of local restaurant cheeseboards.

“Cheese is very creative. Every day the cheesemaker has to worry about the milk. It’s a living thing. You have to be in touch with every element of the terroir,” Hatch says of the weather, seasons, and natural influences on sheep, goat, and cow’s milk. That’s why geographic boundaries — Marin, Sonoma, Mendocino — fall to the wayside when discussing local cheeses.

Because from Point Reyes to northern Boonville, it’s more about seasons and styles than the permeable borders between dairies. “Cheese is like wine. It changes every time it’s made. Some may change from season to season with what the animals are eating, using different cultures. You have to know your milk,” she says.

“But it’s also like a child. You have to constantly take care of it.”

What may have most defined the local cheesemaking business in the last five years, Hatch says, is a significant consolidation that brought in international ownership, something she is ambivalent about.

“When Sue and Peggy sold, I was devastated,” says Hatch of the sale of Point Reyes-based Cowgirl Creamery by founders Sue Conley and Peggy Smith to Swiss dairy processor Emmi in 2016. “We all started at the same time,” says Hatch, wistfully. Six months prior to the Cowgirl sale, local goat dairy Redwood Hill Farms sold to Emmi as well. But two years later, Hatch sees opportunity in the corporate cash infusion.

“Now there is more opportunity to make more cheese. There’s more equipment they couldn’t have bought to make cheese locally with good milk,” says Hatch, pulling out Cowgirl Creamery’s newest cheese, called Hop Along. The young, cider-washed rind is creamy and rich with a hint of tart cider flavor.

Some smaller cheesemakers have suffered as milk prices have gone up, spaces available for cheesemaking have become harder to find, and the very real challenges of artisan cheesemaking have come to light.

“Regulations are tougher, finding space is difficult, and it’s a lot of work for very little money in a very competitive market,” says Vivien Straus, the creator of the California Cheese Trail (cheesetrail.org), which promotes artisan cheesemakers and family farmers. Straus, who grew up on her family’s dairy farm in the rural Marin town of Marshall, sees hope, though. “Some will survive and some won’t. God, it’s a lot of work, but people keep trying. All the cheeses here are so different and so amazing. The whole world looks to us for our cheese.”

Along with Wisconsin and Vermont, Northern California — specifically Sonoma and Marin — are the big leagues of cheesemaking, says Keith Adams, partner and cheesemaker at Sebastopol’s Wm. Colfield Cheesemakers. “We’re persistent and we believe in what we’re doing. You have to operate at a very high level to compete with those who’ve been here a lot longer,” says Adams, who still considers himself a newcomer after two years in business.

Artisan cheesemaker Sheana Davis, whose Delice de la Vallee fresh cheese is a favorite with renowned chef Thomas Keller, agrees. “Some of the smaller producers are struggling to find a marketplace for their cheeses, based on price point, as it is hard to compete with the larger companies.”

In the end, however, places like Oliver’s and the Petaluma Market continue to be champions for local cheesemakers, offering up a wide variety of sheep, cow, goat, and even buffalo milk cheeses at a variety of prices.

“Artisan cheese is expensive, and not everyone can try it,” says Hatch, who believes that great cheese should be accessible to as many people as possible. “I look at what is most exciting,” she says of cheeses that she puts on sale at Oliver’s each month. “I want to give everyone an opportunity. I might be opinionated, but I know what I give you is the best thing for the best price.”

To learn more about all of these amazing cheeses, and for a chance to taste them all in one spot, check out the 13th Annual California Artisan Cheese Festival, March 23-24, 2019. The Festival events happen throughout Sonoma County, including Farm Tours, Seminars at the Flamingo Conference Resort and Spa, Cheese, Bites & Booze! at the Jackson Family Wines Hangar at Sonoma Jet Center, and the popular Artisan Cheese Tasting & Marketplace at the Sonoma County Fairgrounds with over 22 artisan cheesemakers under one roof!

The post Great Local Cheeses To Try, According to Madame de Fromage appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

The best thing about winter rain? Waterfalls!

The post Where to See Waterfalls on The North Coast appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

With its abundance of public parkland and open space, the North Coast is too full of gushing streams and cascading creek flows to mention them all, but a short list would include Sonoma Creek Falls in Sugarloaf Ridge State Park; Alamere Falls in the Point Reyes National Seashore; the Fern Canyon falls in Russian Gulch State Park; and Chamberlain Creek Falls in the Jackson State Demonstration Forest.

The Mount Tamalpais Watershed boasts several well-known waterfalls, including Carson Falls and Cataract Falls. Nearby, in the Baltimore Canyon Open Space Preserve, Larkspur Creek produces the Dawn Falls.

There are seasonal tidefalls at Stengal Beach and Salal Creek that flow into the ocean at The Sea Ranch; a creek waterfall deep inside Pomo Canyon State Park near the Sonoma Coast and another at Armstrong Redwoods State Natural Reserve; plus a stunning falls of the bluff the Point Arena-Stornetta Unit of the California Coastal National Monument in Point Arena.

Descriptions of a few favorite falls follow…

Sonoma Creek Falls

Sugarloaf Ridge State Park, Sonoma County

For an easy-access, quick fix, there’s no better choice than the sweet canyon waterfall right here in Sonoma County that gushes forth during winter rains amid huge boulders and greenery. The 25-foot waterfall has been popular of late, drawing weekend crowds who revel in the refreshing results of a wet season.

The falls can be reached in as little as a third of a mile via the lower Canyon Trail, if you are able to get one of very few parking spots in pullouts along Adobe Canyon Road beyond the Goodspeed Trailhead. It’s a very level path to and from the falls. More parking is available up top, near the park visitor center, where the upper Canyon Trail offers a 450-foot drop down to the falls. The walk is just under a half-mile in each direction, though the return trip is a fairly steep climb up.

Those who prefer a longer trip through the redwood canyon can take a 2-mile loop that starts down the Pony Gate Trail for a little over a mile before it links up with the Canyon Trail and aligns with Sonoma Creek, taking visitors up into rocky canyon from which the waterfall springs. The hike takes about an hour.

The park is located at 2605 Adobe Canyon Road, off Highway 12, in Kenwood. An $8 day use fee applies ($7 for seniors). Dogs are not allowed on trails.

Alamere Falls

Point Reyes National Seashore, Marin County

The trek to Alamere Falls, a cascading coastal falls that bleeds over a slick, shale bluff onto an ocean beach, is a 14- or 16-mile round-trip, depending on the route. But rewards await in the spectacular finale of Alamere Creek, as it stair-steps to the bluff edge 40 feet above the beach, then pours over the mossy rock face to the ocean below. Alamere is a rare “tidefall” that crests the edge of the continent near the southern end of the national seashore, also offering gorgeous coastal views that, on clear days, take in the Farallon Islands. Inland trails include wooded walks through tree canopies, opening onto more exposed trails along the bluff.

Though countless visitors have accessed the waterfall over the years by scrambling down an unstable cliff alongside, national park personnel ask all hikers to reach the falls via Wildcat Camp, a bluff-top campground about a mile north of the falls. Hikers must traverse a mile of Wildcat Beach to get to the falls and then return to the trail, requiring careful consideration of tide and surf conditions. Do not go at high tide.

For North Coast residents, the most efficient and least crowded route starts inside the park at the Bear Valley Visitor Center, 1 Bear Valley Road, Point Reyes Station. Head coastward along the Bear Valley Trail to the Coast Trail, and then south to Wildcat Camp, a trip of about 6 1/2 miles. It’s another mile south on the beach to reach the falls.

A second, far more challenging option, starts near Five Brooks Ranch, 8001 Highway 1, Olema, beginning on Stewart Trail, taking hikers 6.7 miles to Wildcat Camp along numerous switchbacks with significant elevation gains.

The trip from the Palomarin Trailhead farther south, at the end of Mesa Road in Bolinas, is also an option, though it’s the most accessible trailhead for residents of the Bay Area and, thus, very popular. Also, as the northbound trail approaches Alamere Falls well before Wildcat Camp, it brings with it the temptation to climb down the unstable bluff along a now-closed trail. To Wildcat Camp, it’s about 5.5 miles, with another mile walk on the beach.

Poison oak is present along some of the trails. Dogs are prohibited on all routes.

Fern Canyon Trail

Russian Gulch State Park, Mendocino County

Though a popular Mendocino Coast walk, there is nonetheless something intimate about the hike up Fern Canyon to the 36-foot waterfall in Russian Gulch State Park. Delicate ferns lining the canyon and woodland trees in every shade of green draw visitors onward as they follow meandering Russian Gulch Creek along the canyon floor. You can get right up close to the broad stone face of the waterfall and stand amid fallen trees, or hike above the falls, taking care not to slip on wet rocks.

Russian Gulch State Park is located at 12301 North Highway 1, about 2 miles north of the town of Mendocino. The trail starts at the east end of the campground and follows an old logging road with crumbling asphalt for the first 1.9 miles. A bike rack marks the point where the flat, paved trail starts to incline, offering two alternate, hiker-only routes to the waterfall — one a straight, out-and-back leg 0.8 miles long, for a 5.4-mile round-trip, and the other a 1.7 mile loop, for a total 6.5-mile walk. Day use fee of $8 applies. No dogs permitted.

Chamberlain Creek/ Waterfall Grove Trail

Jackson State Demonstration Forest, Mendocino County

This remote, narrow waterfall east of Fort Bragg draws visitors deep into Jackson State Demonstration Forest off Highway 20. Even if there were no waterfall to see here, the short hike into virgin redwood forest is like a trip into an enchanted land, where brilliant green moss coats the rocks and fallen timber amid majestic redwoods have stood tall for centuries. It’s easy to imagine fairies flitting about in the streams of sunlight that break through the overhead canopy, or hiding amid plentiful ferns that blanket the ground and the rock face down which Chamberlain Creek cascades into a small pool.

To reach the trail, turn north from Highway 20 onto Road 200 at Dunlap Conservation Camp, located just over 16 miles east of Fort Bragg. Follow the road, bearing left, past the point where it branches into an unpaved road. At 4.7 miles north of Highway 20, there is a rustic wooden railing and stairway leading down into the woods along switchbacks that open onto the single-track trail. Park here. The waterfall is located about a third of a mile along, but the path continues northward, climbing back up to the road at a point about a half-mile from the steep staircase for a total trip of about 3 miles. Free. Leashed dogs permitted.

The post Where to See Waterfalls on The North Coast appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

An environmental battle threatens the decades-old partnership between the National Park Service and ranchers at Point Reyes.

The post Point Reyes Ranchers: Point of Conflict appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

Photography by Kent Porter.

Storm clouds shadowed Ted McIsaac as he shifted his battered 1994 Chevy pickup into four-wheel drive and bounced along a muddy track over hills cloaked in brilliant green grass.

His border collie Rollin trotted alongside while McIsaac made a routine morning recon of his 2,500-acre Point Reyes ranch to scan the slopes near and far for his 160 head of pure black cattle. To the west, the dark spine of Inverness Ridge framed the horizon, and two miles beyond winter surf pounded a wild coastline.

“You rely on Mother Nature. She rules your day,” said McIsaac, 65, a lean, sturdy man with a creased face and square jaw. A fourth-generation rancher, he’s accustomed to the vagaries of weather, especially spring rains that can make or break a cattleman.

But a much larger storm now hangs over the remote Point Reyes peninsula, where a legal fight triggered by three environmental groups has profoundly unsettled life for McIsaac and the 23 other families who operate ranches on the federally protected landscape.

Theirs is a way of life often as rough as the relentless waves crashing at the edges of this timeless headland. And they believe the future of ranching is at stake in the 71,000-acre Point Reyes National Seashore, where pasture for beef and dairy cattle exists side by side with wilderness, both shielded from development in a unique preserve established by the federal government at the ranchers’ behest more than 50 years ago.

President John F. Kennedy, convinced it was some sort of charmed West Coast Cape Cod, created the national park after ranchers and environmentalists fearful of intense development pressures banded together to stop the encroachment of subdivisions on Point Reyes.

As part of the deal, the ranchers insist they were made a promise specifically designed to endure: They could remain as long their families were willing to work in the wet, cold and wind of an unforgiving landscape.

Point Reyes and its landscape are the center of an unfolding dispute that ultimately seeks to define the nature of the landscape in America’s national parks: Can the treasured public scenery accommodate the country’s ranching tradition?

The lawsuit, which has drawn wide attention to the region, does not directly seek removal of the ranches but raises fundamental questions about the purpose of the seashore. It claims that the ranching that began here more than 150 years ago — and continues under leases with the federal government — is harming the wildland and wildlife the park is also supposed to safeguard.

If studies show cattle are harming the seashore they could be prohibited, said Jeff Chanin, a San Francisco attorney who represents the plaintiffs. Federal court rules require the two sides to discuss a possible settlement that would avoid a trial, he said, and a conference is set for May.

The park, just an hour north of San Francisco, includes thick conifer forests, miles of unspoiled beaches, wetlands teeming with birds and coastal bluffs where herds of massive tule elk roam. About 2.5 million visitors, including hikers and backpackers, are drawn to the spectacle every year.

Over decades, thousands of grazing cattle have trampled that habitat and polluted those waterways, say the environmental groups that sued the National Park Service in February, saying none of the ranch leases, many on 1-year terms, should be renewed without further study of their impact.

“That’s a public landscape,” said Huey Johnson, a former California secretary of resources and founder of the Trust for Public Land. He now heads the Mill Valley-based Resource Renewal Institute — one of three parties that filed the lawsuit.

Johnson said the Park Service’s management of the ranches is a travesty.

“We’ve got pastures of mud and manure instead of wildflowers,” he said.

However, for the park’s ranchers and their many allies, who extend from West Marin to Capitol Hill, the lawsuit threatens not only a way of life but a nearly unprecedented experiment in the history of the national park system – the same network that includes beloved spots such as Yosemite and Yellowstone.

With the exception of an Ohio park, no other place in the country allows working ranches within national park boundaries.

The pivot by some environmentalists against ranches in the seashore threatens to undermine the foundational deal on which the park was established, said Rep. Jared Huffman, the whose North Coast district takes in the park.

He called the lawsuit a “frontal assault on any continued agriculture in the Point Reyes National Seashore.”

“We are not going to let these ranches and dairies go on my watch,” said the Marin County Democrat, a former environmental attorney.

Were it not for the lawsuit, this would be a pretty good season for Point Reyes ranchers. The wet winter and spring have delivered a plentiful grass crop to feed their herds and a respite from the worries of several drought-plagued years that nearly doomed some outfits.

In spring 2014, McIsaac came within 45 days of going broke after buying hay most of the year to feed his cattle. Late-March rains bailed him out.

“We raise cattle but what we really do is harvest grass,” he said.

McIsaac, who carries a cigarette pack in the pocket of his fleece vest, is the great-great-grandson of a Civil War veteran who came to the Point Reyes peninsula in 1865 as California’s dairy industry — now a $9 billion a year enterprise — was getting rooted in a lush landscape once described as “cow heaven.”

Home for his family is a pale-green, two-story farmhouse, part of it built in the 1880s, all of it crying for a coat of paint. One end of the house burned in 1955 and was upgraded, but since he sold the ranch to the government in 1983, McIsaac, like the other ranchers on short leases, has little ability to borrow money and gains no equity from making improvements.

Ranchers throughout the park are in the same boat, and few complain about it. Instead, they put greater stock in their ability to diversify and broaden their future agricultural options, adding other consumer products to bolster their finances.

As far back as the 1920s, Japanese farmers grew peas and Italians raised artichokes on what is now parkland next to Drakes Estero, the large tidal waterway at the heart of the seashore.

Fast-forward nearly a century and the larger region is renowned in the food world for its grass-fed beef and organic dairy goods, launching famed Bay Area labels such as Niman Ranch, the natural meat purveyor, and Cowgirl Creamery, the artisanal Point Reyes cheesemaker. But without 20-year leases, ranchers say, they are unable to borrow money to make the improvements needed to cash in on such trends in agriculture. Jarrod Mendoza, who milks about 200 cows on B Ranch near the tip of the Point Reyes peninsula, said he needs financing to rebuild an old wooden barn that blew down during a storm in March. “You don’t want to see the book closed,” said Mendoza, whose great-grandfather acquired the 1,200acre ranch in 1919.

The trio of environmental groups suing the Park Service, however, claim that a broader range of farming at the seashore ranches – including chicken, pig and row-crop production, for example – could result in more conflicts with wildlife and wilderness in the park.

Their lawsuit has targeted the renewal of ranching leases thathey fear could pave the way for broader agricultural operations.

That process, said Jeff Miller, of the Oakland-based Center for Biological Diversity, another of the plaintiffs in the case, is “predetermined”

to favor awarding the ranchers with the long-term leases they seek.

“It hasn’t asked whether ranch leasing is appropriate,” he said.

The suit, citing reports by the Park Service, contends that grazing cattle have polluted waterways such as Drakes Estero with manure and degraded the habitat of threatened or endangered species, such as coho salmon and California red-legged frog.

Ranchers bristle at claims their operations are damaging a land- scape their families have occupied for generations.

Nicolette Niman, who runs 175 cattle on a 1,000-acre ranch in Bolinas at the southern tip of the seashore, asserted in her book, “Defending Beef,” that small-scale, well-managed ranches are good for the land. Periodically moved from one pasture to another, cattle trim the grass, press seeds into the soil and fertilize it with their urine and manure, said Niman, who bills herself as “an environmental lawyer and vegetarian turned cattle rancher.”

“Human activity isn’t hostile to the principle of preserving the land,” she said. The prehistoric Coast Miwok maintained the peninsula’s coastal prairies by setting them on fire, and cattle grazing

continues that purpose, Niman said. An end to ranching would diminish the landscape and the community, Niman said.

“The beautiful, big, open areas you can walk through” would shrink under the advance of woodland, eliminating grasslands where hawks and eagles feed. Local schools, churches and businesses would lose the support of ranching families, who are “the bedrock of West Marin,” she said. “It would be transformative.”

Allies in the worlds of land conservation and academia have chimed in to support the ranchers’ place in the park.

“You can have wild spaces and agriculture side by side,” said Laura Watt, a Sonoma State University environmental historian whose 15- year study of the seashore has focused on the region as a working landscape, with human uses and wild habitats closely intertwined.

The opposite view, one held by the plaintiffs, Watt said, is an “absolutist” division of farm- and wildland that insists parks must minimize human presence to ensure “zero impacts” on the landscape.

The mix of ranching and wildland is “part of the charm at Point Reyes” and ought to be preserved, she said.

In the real world, ranchers and their allies are also worried what a smaller footprint in the park or constrained operations would mean for the future of North Bay agriculture. Prominent Marin County conservationist Phyllis Faber, who Co-founded the Marin Agricultural Land Trust, notes that the seashore ranchers were pioneers in open space-protection in 1960s when they agreed to sell their land to the government. Farm fortunes were waning at the time and the urban Bay Area was booming, putting immense pressure on peninsula landowners to sell out to developers.

But Faber, 88, now fears that move may turn out to be the “death knell” for the ranchers.

Congress could settle the matter, and possibly stifle future lawsuits, by reaffirming the place of ranching in the seashore. “It would save the ranchers a lot of heartache,” she said.

On a clear day, Rich Grossi and his wife, Jackie, can see the ocean from the picture window of their home on M Ranch — one of 14 historic “alphabet ranches” in the seashore.

When the fog rolls in, as it does about 200 days a year, visibility shrinks to a few feet and patrols of 1,200-acre spread become a bit dicey.

A visitor would call the setting spectacular, but Grossi, hardworking at 76, scans the terrain with a different eye, seeing ranch chores almost everywhere he looks. Fence repairs are endless.

“One night I lay in bed and tried to figure out how many gates we had,” he said. “I lost count.”

Still, the business is one the Grossis plan to pass down in their family. Their daughter, Diane Turner, lives in the house next door and represents the fourth generation on M Ranch.

“We’re growing food for people,” said Turner, 50. “Not like living in town. It’s a whole ’nother world.”

The Grossis admit to being rattled by the standoff over ranching in Point Reyes. It is the latest place where tough-minded environmentalists have called for greater scrutiny over livestock grazing on public lands in the western United States.

The Center for Biological Diversity, one of the more successful and well-known among those interests, specializes in lawsuits aimed at protecting endangered species. The group’s website touts that 93 percent of its cases “result in favorable outcomes.”

The third plaintiff involved in the Point Reyes suit, the Western Watersheds Project, includes among its litigation victories a 2007 federal court ruling that threw out rancher-friendly grazing regulations established by the George W. Bush administration on more than 160 million acres of public lands in 11 states.

“They’re not playing games,” said Mclsaac, who serves as president of the Point Reyes Seashore Ranchers Association. “That’s worrisome.”

Of particular concern for the ranchers and their allies is the Park Service’s shifting stance on the place of agriculture in the seashore. The worries were fueled by a bruising, 2-year battle the agency fought to close a popular oyster farm in the seashore in 2014. The case, which oyster farmer and Point Reyes rancher Kevin Lunny lost, went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

That case was different because Lunny purchased the property knowing his lease would expire. Still, it proved a searing, divisive experience for a West Marin community that prides itself on the value of both locally grown food and wild places.

Ranchers steer clear of faulting the Park Service, which is their landlord, but their allies question its commitment to agriculture. Lunny’s farm, they say, was railroaded out of the seashore after the agency became determined to end an 80-year history of oyster cultivation in 2,500-acre Drakes Estero.

In the case of the beef and dairy ranchers, Watt suggested the oyster war could predispose the Park Service to settle for “some kind of compromise” on leases rather than wage a long legal battle.

Nevertheless, the parks agency, even during that prolonged fight over the Drakes Bay Oyster Co., has sought to clarify that the seashore’s ranches are not in its sights and have a solid place in the park.

“Ranching is integral to our history and to our future here at Point Reyes National Seashore,” Park Superintendent Cicely Muldoon said in a press release in April 2014 at the start of a lengthy planning process. “For more than 50 years, ranchers and the park have been working together. This plan is an opportunity to build on that past, address current issues and strengthen our shared stewardship of these lands.”

The pact struck by ranchers years ago in the seashore’s formation ought to provide some reassurance that grazing and wilderness can continue to exist side by side, Muldoon said in an interview. “I don’t see it as a conflict at all at Point Reyes,” she said.

Environmental groups have succeeded before in removing cattle from a national park in California. A 1996 lawsuit by the National Parks Conservation Association culminated in a settlement that stopped grazing on Santa Rosa Island, which had become part of the Channel Islands National Park off the Santa Barbara County coast 10 years earlier.

The association, a group that acts as an environmental watchdog, parks lobbyist and sometime-litigant against the Park Service, said cattle grazing in that instance was harming the island’s ecology, along with a trophy-hunting operation.

The group also pushed aggressively for the ouster of the Drakes Bay Oyster Co., noting that the estero in which it operated was designated to become wilderness in 2012 when the farm’s 40-year permit was set to expire.

But in the current case, the group is backing agriculture in the ranch planning process.

“We support the combination of ranching and the seashore,” said Neal Desai of the National Parks Conservation Association. “We think that’s possible.”

Also supporting the ranchers is the powerful California Cattlemen’s Association, which represents the state’s $3 billion beef cattle industry.

The group has “butted heads plenty of times” with the Center for Biological Diversity in and out of court, said Kirk Wilbur, director of government affairs.

The latest lawsuit was no surprise, he said, in the wake of the oyster farm’s ouster. “It’s a pretty transparent attempt by radical environmental groups to get grazing off the landscape,” he said.

The plaintiffs insist that is not the goal of their lawsuit, calling such assertions “sensationalist.”

“There’s no call to an end to ranching in the litigation,” said Chance Cutrano of the Resource Renewal Institute, the group headed by Johnson, 83, the former state resources secretary and a widely respected figure in environmental circles.

Instead, the claimants want the Park Service to assess the impacts of ranching and devise a plan to address them, Cutrano said.

Whether ranching continues and what the conditions might be is “not up for us to decide,” he said.

For nature lovers savoring the spring wildflowers at Chimney Rock, panoramic views from Mount Vision and the stunning vista at 11-mile Point Reyes Beach, the national seashore offers the balm of wilderness. But those visitors, according to the Park Service’s own description, have “happened upon one of the earliest and largest examples of industrial-scale dairying in the state of California.”

Hikers heading to the four backcountry campgrounds feel they have found refuge from urban hubbub, but all of them are located on the site of vanished dairies. At Sky Camp, located near the summit of 1,407-foot Mount Wittenberg, large fir, cypress and eucalyptus trees mark the location of a dairy that milked 75 cows and made a ton of butter a month in 1901, according to local historian Dewey Livingston’s book, “Ranching on the Point Reyes Peninsula.”

When the national seashore was established in 1962, there were ranches and roads throughout the peninsula. Many have since been erased by the Park Service.

“The wilderness area is an artificially created and managed setting of pristine-ness, disregarding the actual history of the place,” Watt, the Sonoma State historian, said in a 2002 article.

Wild or not, it was a landscape and a way of living that called McIsaac back four decades ago, a few years after he’d bolted from the family ranch, convinced he never wanted to look at another milk cow.

He returned in 1975, working for his father, and he took over the ranch about 15 years later.

“I can’t imagine doing anything else,” he said, his stained work jeans and worn ball cap evidence of a long days spent outdoors.

The rhythms of daily life for McIsaac and fellow park ranchers are largely imposed by sunup-to-sundown chores and the harsh elements. Point Reyes is the second-foggiest place in North America, behind Grand Banks, Newfoundland, and the windiest spot on the Pacific Coast.

But beyond the weather, when ranchers find time these days to meet up, their talk inevitably turns to the lawsuit over their leases.

The discussion is filled with uncertainties, weightier even than those that usually dog them. Families with four and five generations of working the land worry that their dream of passing it on to their children and grandchildren won’t come to pass.

Rich Grossi, who has no plans to retire, said his family has put off talking about who will take over M Ranch when he does step back. “We’re kind of cooling it now to see if we’ve got a leg to stand on,” he said.

Settled in the comfortable ranch house kitchen, Jackie Grossi said the future is out of their hands.

“We don’t know where it’s going to lead,” she said. “It’s heartbreaking.”

The post Point Reyes Ranchers: Point of Conflict appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

Where to eat in Tomales, Point Reyes, Marshall and along the Sonoma Coast

The post Sonoma Coast Dining: Tomales, Point Reyes, Marshall appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

Need a little summer getaway? BiteClub heads for the beach, stopping to pick up plenty of provisions along the way.

Need a little summer getaway? BiteClub heads for the beach, stopping to pick up plenty of provisions along the way.

Santa Rosa to Tomales: Passing through Petaluma, head out toward the town of Tomales. It’s an incredibly scenic ride through golden hillsides dotted with eucalyptus groves. About 30 minutes out, you’ll enter this cozy historic outpost that’s home to the Tomales Bakery. And, uh, not a whole lot else. Best known for their fresh-made breakfast pastries, the shop opens at 7:30am, usually to a waiting crowd. By early afternoon, the shop is pretty picked over, but you can usually find a pizzetta or two to tide you over until you hit Tomales Bay. Need provisions? If you’ve just gotta get a sandwich, there’s also a deli next door with coffee and the usual lunchtime suspects. (But hey, you’re holding out for the oysters!) Tomales Bakery, 27000 Highway 1, Tomales, 707.878.2429. Open Thursday through Sunday from 7:30am until they run out of food.

Hog Island Oysters: As you get to the bay, the signs for BBQ oysters abound. If you’re feeling adventurous (and have made a reservation well in advance) Hog Island Oysters sells fresh-from-the-bay oysters onsite and has a popular picnic spot right on the bay for grilling them up yourself. Not lucky enough to get a picnic spot, it’s worth crunching over the oyster shells in the parking lot and stopping in just to see the “Farm” where the oysters spend their last 24 hours in huge tanks getting cleaned. Note: You can’t buy prepared oysters here (aw shucks!) The Farm: Open Tuesday through Sunday from 9am to 5pm; located on Highway 1 in Marshall, about 15 minutes north of Point Reyes Station and 45 minutes south of Bodega Bay. 415.663.9218.

The Marshall Store: Don’t let it’s shabby looks deceive you. Inside this oyster shack are some of the best oysters to be found in the area. Barbequed, Rockefellered or raw (or all three), they’re prepared while you wait and served up with hearty local bread for dipping all that juice. And the best part? The view is free. Located on Highway 1 in Marshall, Open seven days a week, 10am to 6pm.

ADDED Nick’s Cove: If you’ve got a little more time, don’t miss stopping at the new Pat Kuleto project–a reimagined Nick’s Cove. The menu includes plenty of oysters, along with the Cove Oyster PoBoy, a Niman Ranch chuckburger, Marin Sun Farms Beef Carpaccio and fish and chips made with local Petrole sole. Plus, should all those oysters leave you feeling a bit randy, you can grab your cutie and head to a the remodeled cottages along the beach. Nicks Cove and Cottages, 23240 Highway 1, Marshall.

ADDED Marin Sun Farms Butcher Shop: Sustainably raised beef from the Marin ranches is sold at the Pt. Reyes butcher shop to the delight of meat-eaters from through the Bay Area. Though you can get this high-quality meat at plenty of local restaurants, the butcher shop is one of the only retail sellers in the North Bay. Plus, farm fresh eggs. Nothin’ better. 10905 Hwy 1, Point Reyes Station, 415.663.8997, ext. 204

Tomales Bay Foods: Yes, you have reached nirvana. Combining the Cowgirl Creamery, an mini indoor farmer’s market, a case of prepared salads and lunch nibbles, a wine shop and coffeehouse, this is picnic bliss. On weekends, you’ll likely have to fight your way through the throngs of city folk to pick up some Cowgirl cheese and organic nectarines, but oh, how worth it. Don’t miss watching the curds getting stirred through the big window at the back of the store. Point Reyes, 415 663-9335. While in town, don’t miss Marin Organics’ Pt. Reyes Farm Market and nearby Bovine Bakery.

The post Sonoma Coast Dining: Tomales, Point Reyes, Marshall appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>