The Point Reyes ranch has been in the family since 1946. After a reluctant settlement deal, the family gathered for a bittersweet reunion and final roundup.

The post Point Reyes Family Says Goodbye to Cherished Ranch After Years of Legal Battles appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

Early dawn on Point Reyes brings another sunrise without a sun, the May fog shrouding this Saturday as winds whip up like they often do out on the peninsula.

“It’s all I’ve ever known,” says rancher Kevin Lunny. He’s talking about the wind, the light, the smell of cows, the scent of salted air off the sea — almost every detail in his life — as he drives a 4×4 into the pasture where his grandfather first set foot in 1946.

An executive at Pope and Talbot in San Francisco, Joe Lunny Sr. was a steamship man, not a farmer. But after buying a run-down dairy on the Historic G Ranch, he learned, often the hard way, from old family ranchers nearby, like the Kehoes and the Mendozas, who had worked the land long before he arrived. His son, Joe Lunny Jr., who was 17 at the time — he’s now 94 — remembers, “I came out here as greenhorn as you can be.”

Over these past few weeks, everything Kevin Lunny does, whether closing a pasture gate or fixing a fence wire or taking an evening walk down to Abbotts Lagoon with his wife Nancy — he keeps asking himself, will this be the last time?

Today, at least, one thing appears sure: This is the final cattle roundup at Lunny Ranch. The last time he’ll ever bring cows into corrals and separate them. He’s known this day might arrive sooner than later, for years now.

“But it’s still hard,” he says.

More than a decade ago, when he lost a long-shot bid to renew the federal lease inside Point Reyes National Seashore for his Drakes Bay Oyster Company, he had a premonition this day might come. After the seashore was created in 1962, with provisions for pastoral and wilderness lands, the longtime ranching families were reluctant to sell their land to the federal government, even with agreements to lease the land back.

Over the decades, those agreements came increasingly under fire from environmental groups who want more of the park turned over to wilderness and wildlife. After years of lawsuits and mediation between ranchers, environmental groups, and the National Park Service, which owns the land, the park is effectively shutting down the farm Lunny grew up on, one of a dozen set to close by next year under a voluntary buyout brokered by The Nature Conservancy.

Lunny, a frontman in many of the biggest fights over the seashore in the past decade, doesn’t want to argue over the details anymore. He held out as long as he could. Finally, his father came to him and said, “I think we have to come to a yes. I don’t want to see it kill you.”

In January, he was the last of 12 ranchers to sign the settlement, which includes a reported $30-million payout to the ranchers who agreed to leave the land forever by next spring.

Now, Lunny looks out on the pasture where his grandkids, other family, and old friends make wide sweeps on dirt bikes, horseback, and 4x4s, leading the cattle toward the corrals.

“We’ve never had this many people to gather cows in our life,” he says. “It’s really kind of everybody in the family coming together. It’s very emotional for everybody. It shows you how this place has been meaningful for generations.”

His daughter Brigid Mata, who has worked the farm since she was a child, says she originally thought maybe the last roundup should just be small and super-intimate. “But my dad said, you know, everyone has memories here. Everyone wants to be a part of it.”

On this final roundup, there are 90 mother cows, 30 bred heifers, 85 calves — many that will relocate to a pasture in southern Oregon for now. And 55 2-year-olds going to slaughter.

Over the next few hours, friends and family from as far and wide as Tennessee, Washington and all over California, will lend a hand helping sort cattle while a vet does pregnancy checks on mother cows. Mata will attach new ear tags on the cows going to Oregon, and Nancy Lunny will log every detail from the vet checks in her notebook. Eventually, empty boxes of doughnuts make way for an open-pit barbecue firing up. It feels like a family reunion, with all the hugs and back-slapping and kids running around.

“On the outside we might be laughing and smiling and carrying on, but on the inside, everyone is sad,” says Kevin Lunny.

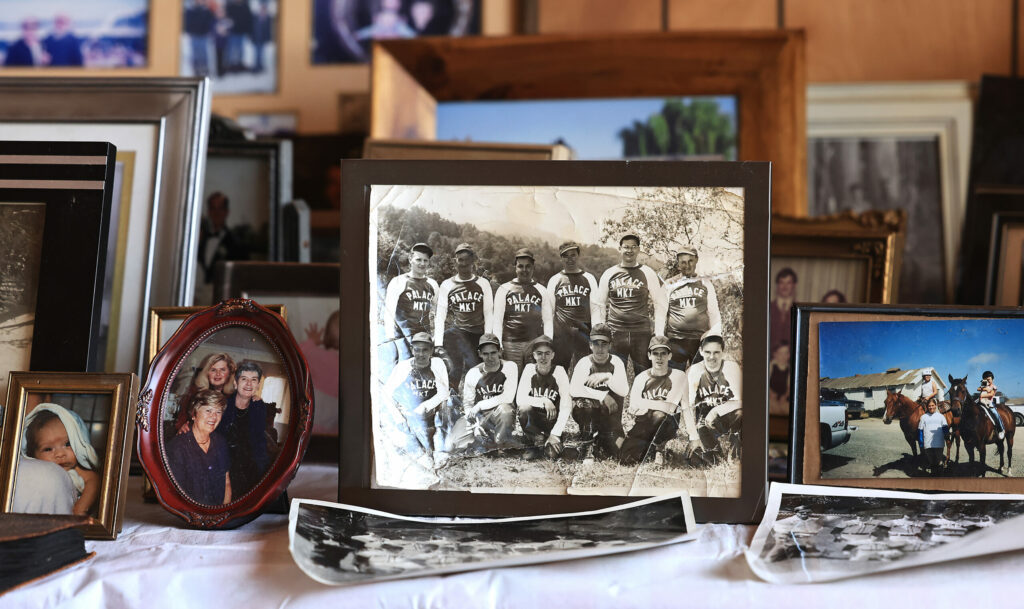

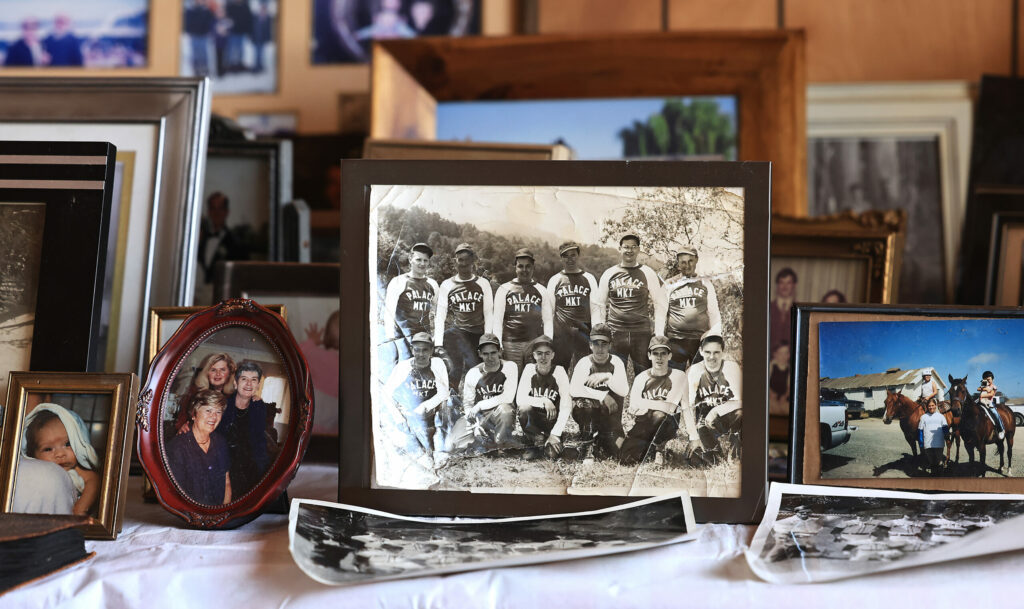

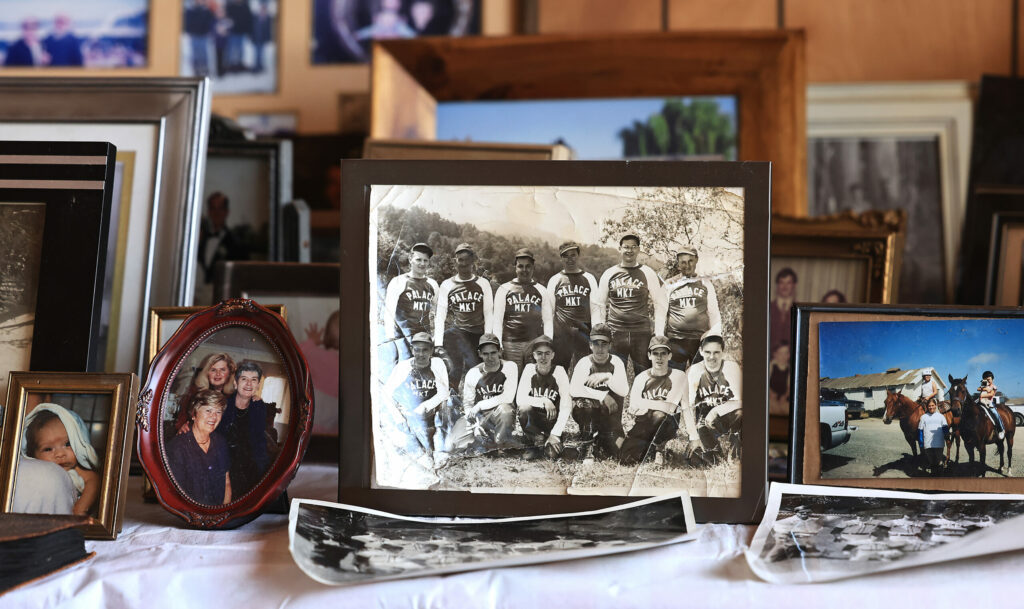

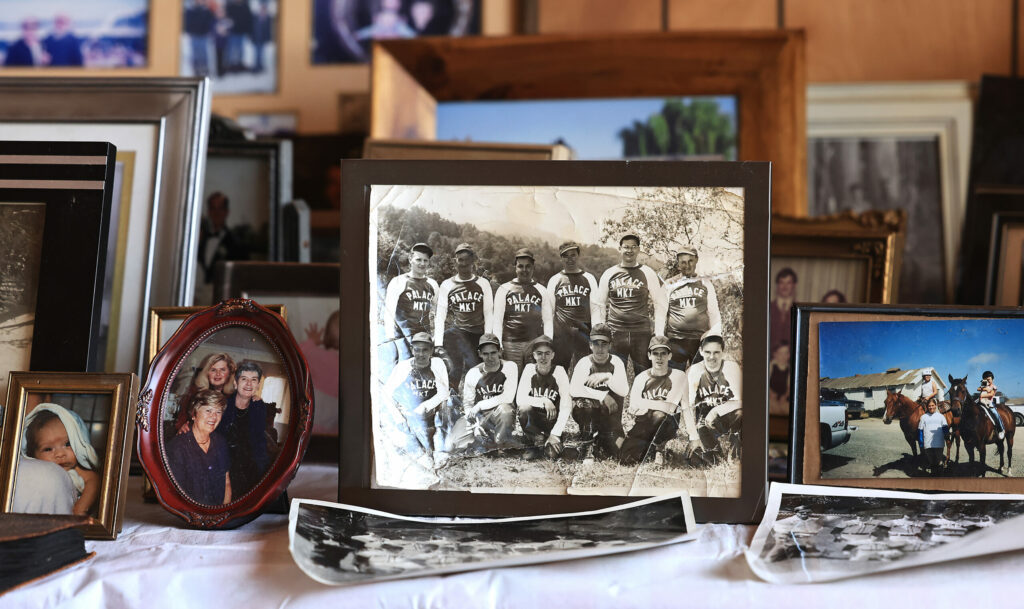

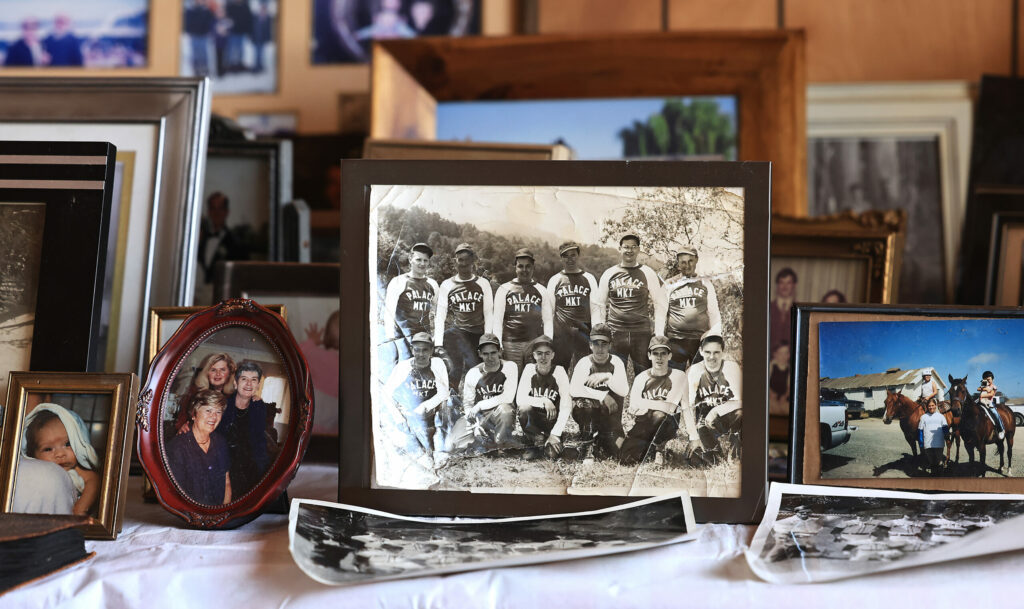

His father, Joe Lunny Jr., is taking it the hardest. He’s watching from afar, on the patio of the main house. As people park and walk up the driveway, they stop to pay their respects as if giving their condolences at a funeral. Joe leads them through a room with walls filled with family photos and deer mounts. Nearby, framed on the wall, an old Press Democrat story headline reads, “Ranching in Paradise.”

Over the years, it became anything but that.

“I thought I would die here one day,” says Joe Lunny Jr., choking back tears as he reaches out to the land with one arm.

Will he ever return to visit?

“Why would I?” he says.

By this time, in the thick of summer, Kevin and Nancy Lunny plan to be settled down in their new home on 10 acres near Auburn. His father will split time with them and his sisters, who live in Penngrove and McCloud near Mt. Shasta.

On the farm outside Auburn, there’s a pond stocked with bass and bluegill that his grandkids love to fish. Kevin Lunny thought he would have a hard time adjusting to such a quiet place, without the constant sound of the ocean and harsh winds he grew up with in Point Reyes. But a creek running through the property “that babbles year-round” has filled any void. He also kept a few cows, because he says it would be hard to live without them, and he has a barn.

Lunny has promised to stay involved in the ongoing battle over ranching in the park and help other ranchers in need. Lately, there have been rumblings that bureaucrats in Washington might reverse the deal that ended ranching in the park. If that happened, would he be interested in coming back to Point Reyes?

“In a heartbeat,” he says. “We’d do it in a second.”

But he already spent the money.

“We signed a contract,” he says. “We committed never to come back.”

The post Point Reyes Family Says Goodbye to Cherished Ranch After Years of Legal Battles appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

Two Mendocino and West Marin destinations were listed in a Fodorś Travel article for once being home to notorious cults.

The post These Mendocino and Marin Properties Were Once Home to Cults appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

Home to many getaway destinations and diverse landscapes, California has also hosted infamous cults over the decades.

A Sept. 23 article from Fodorś Travel, titled 8 Dreamy California Destinations That Were Once Home to Cults, listed a ranch in Mendocino County.

One of the eight destinations is Ridgewood Ranch, located on 5,000 acres of rolling hills, creeks and forests in Willits. The current owner of the property is Christ’s Church of The Golden Rule, formerly known as the cult Mankind United.

Arthur Bell founded the cult during the Depression. Bell — a swindler, especially in real estate — believed the world was under the control of “Hidden Rulers” and “Money Changers” determined to make a “worldwide slave state,” according to the Fodorś article.

Bell convinced many that the only way to avoid this fate was to enter into his cult, Mankind United. In order to join, followers had to give Bell half their possessions and work long hours for low pay in the cult’s hotels, restaurants and ranches throughout the state.

Bell handed over leadership of the cult in 1951 as a result of legal battles and bad press.

Although the cult unraveled, about 100 people stayed and settled on Ridgewood Ranch. The community now “operates a mobile home park, runs (approximately) 200 head of cattle and works with conservation groups like Mendocino Land Trust,” the article stated.

Ridgewood Ranch was also where famous racehorse Seabiscuit died of a heart attack in May of 1947, according to a Press Democrat article from May 21, 2020.

That wasn’t the only Northern California destination listed in the article. Lodge at Marconi, located in West Marin, was a remote location for the Church of Synanon from 1964 to 1980.

According to the Fodorś article, the Church of Synanon has a twisted history. Mickel Jollet, frontman of indie rock group The Airborne Toxic Event, lived on the property as a child. He recounted in his memoir, Hollywood Park, “how children at the Tomales Bay Synanon were taken from their parents at six months old and raised by other cult members in a type of orphanage.”

The Point Reyes Light newspaper “helped expose Synanon as a dangerous cult, winning the paper a Pulitzer Prize in 1979,” the article stated.

Two of the eight destinations listed are in Northern California, but the rest were from the Los Angeles area. These included: Hotel Casa Del Mar, Santa Monica; Al Cove Café & Bakery, Los Feliz; Peace Awareness Labyrinth & Gardens, West Adams; Beachwood Canyon Neighborhood, Los Angeles; Santa Susana Knolls Neighborhood, Ventura County; and Mount Baldy, San Bernardino and Los Angeles counties.

Find the full list at fodors.com.

The post These Mendocino and Marin Properties Were Once Home to Cults appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

Pair your cocktail with an ocean view at these coastal bars.

The post From Marin to Mendocino: 8 Ocean-View Bars To Visit Along Highway 1 appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

We love any excuse to escape to the coast — from Marin to Mendocino — and, of course, Sonoma! Whether it is to reward ourselves with a local beer after a long day of hiking or biking, or toast to a special occasion as the sun sets, a cocktail with a coastal view never gets old. Click through the gallery above to discover our favorite coastal bars.

The post From Marin to Mendocino: 8 Ocean-View Bars To Visit Along Highway 1 appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

90 award-winning wines will be poured at the North Coast Wine & Food Festival. Where does a wine-lover begin? Here are 15 picks to start with.

The post 15 Wines You Must Try at the North Coast Wine & Food Festival appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

We love a great party. On Saturday, June 10, we’ll celebrate the North Coast’s food and wine bounty at The Press Democrat’s North Coast Wine & Food Festival at SOMO Village in Rohnert Park. Over 60 award-winning wineries, pouring 90 Gold Medal wines, and 20 acclaimed chefs, serving up delicious bites, will be the stars of the show.

It’s a must-attend event for any wine lover seeking to discover the best wines from Sonoma, Napa, Lake, Marin, Solano and Mendocino counties. It can also be overwhelming — with so many wines to try in one afternoon, where do you start?

To help guide your palate, here are 15 award-winning wines you must try at the North Coast Wine & Food Festival.

BUBBLES, BABY

J Vineyards and Winery Russian River Brut Rosé

Toast to an afternoon of food and wine tasting with this Best of Show Sparkling. “Seamless from start to finish,” is how the judges described J Vineyards sparkling rosé, and it does have a show-stopping pink salmon color, complemented with flavors of raspberry, blood orange and Marcona almonds.

Gloria Ferrer 2007 Royal Cuveé

A consistent favorite, this Best of Class sparkler is called “Royal” because the first vintage was served to the king and queen of Spain in 1987. It’s creamy with brioche and a bit of lemon, pear, and apple that has helped to define Northern California sparkling wine.

ROSÉ ALL DAY

Taft Street 2016 Russian River Valley Rosé of Pinot Noir

Named the Best of the Best in the North Coast Wine Competition, Taft Street’s rosé was described as being “really pretty…like a spring day, by judges, making it a great and probably popular wine to sip during the festivities.

Three Sticks Casteñada Rosé

Take a cute stubby bottle, a name that rolls off the tongue (Casteñññadaaaa) and shocking pink color — oh and a delicious strawberry and watermelon infused rosé, and you’ve got an award-winning Best of Class wine that judges called “fresh and sassy.” You’ll want to be seen with this in your glass at the festival!

PATIO POUNDERS

Balletto Vineyards Russian River Valley Estate Pinot Gris

An estate pinot gris is a rare treat in Wine Country and Balletto’s wine won’t disappoint. This Best of Class white was described by judges as being lush with stone fruit, pear and citrus, making it a perfect pairing with the abalone tostada to be served by Glen Ellen Star’s Chef Ari Weiswassser.

Dry Creek Vineyard 2016 Sauvignon Blanc

A warm festival day requires a cool wine and sauvignon blanc is it! Dry Creek’s sauvignon blanc received a whopping 98 points from judges, making it Best of Class. Judges didn’t mince their words with this white: “gorgeous, sexy, wild, racy.” Grab a glass and head straight to the Cokas Diko Home Premium Access Lounge to chill.

WICKED WHITES

Anaba Wines 2014 Sonoma Coast Chardonnay

Chardonnay fans rejoice! Your favorite varietal won Best of Show White. If you aren’t a fan of chard, we welcome you on the bandwagon because this isn’t your mother’s butter bomb. Judges shared that it’s “just delicious to drink,” due to its perfect balance of citrus, oak and acid.

Husch Vineyards 2016 Mendocino Chenin Blanc

Chenin blanc has a cult following in Wine Country and Husch won Best of Class for their 2016 release. A fresh and zesty wine, judges noted hints of lemon curd, peach and tropical fruit in this chenin. Pair it with the mac and cheese, featuring local mushrooms, served by boon eat + drink’s Chef Crista Luedtke.

PINOTPHILE PICKS

Folie à Deux 2014 Sonoma Coast Pinot Noir

It wouldn’t be a Sonoma County food and wine festival without pinot noir! This Best of Show Red scored 98 points with judges and was called a “wonderful example of a Pinot Noir.” Chock-full of cherry, there is a touch of spice, cola and toffee that will satisfy even the pickiest of pinot fanatics.

DeLoach Vineyards 2014 Marin County Pinot Noir

Marin County has grapes? Yes, they do! DeLoach won Best of Marin County with their single vineyard designate pinot. This “sexy” wine (as one would expect from a wine by Jean-Charles Boisset) has the qualities of a great pinot: dark plum, cherries and soft baking spices.

RHONE ALONE

Trione Vineyards & Winery 2013 Russian River Valley Syrah

Sonoma County produces beautiful cool climate syrah, including this Best in Class Syrah from Trione. It’s dark, rich, brooding and a little bit rustic with blackberry and truffle on the palate. “Yes, please!” cheered judges in their tasting notes.

Thirty-Seven 2015 Sonoma Coast Grenache

A Carneros-based winery, Thirty-Seven took home three Best of Class awards, including for their latest grenache. This small-lot wine has strong cherry notes with lingering tannins dabbled with baking spices and rose petal. Judges called it “quaffable,” which is a mandatory quality of any festival wine.

BOLD BORDEAUX

B Side 2014 Napa Valley Red Blend

Declared Best of Napa County, this red blend of mainly cabernet sauvignon and merlot was described by judges as “sultry,” “seductive” and “sexy.” It’s a big wine that is perfect to pair with a juicy steak. Look for it at the Don Sebastiani & Sons’ booth.

Brassfield Estate Winery 2014 High Valley Estate Cabernet Sauvignon

Brassfield produced this Cabernet, named Best of Lake County, from atop their estate which overlooks Clear Lake. This “savory, rich, complex” wine is another top choice for a meaty meal. Judges also called it a “party in a bottle,” which we translate into “festival party wine.”

SWEETIES & STICKIES

Navarro Vineyards 2016 Anderson Valley Late Harvest Cluster Select Muscat Blanc

Navarro took Best of Mendocino County for their sweet Late Harvest white wine that judges declared “perfect” and “pure liquid diamonds.” Best sipped with Chef Daniel Kedan’s candy cap mushroom kettle corn.

The Press Democrat’s North Coast Wine & Food Festival is Saturday, June 10 at SOMO Village in Rohnert Park. Tickets start at $50. More information and tickets here: northcoastwineandfood.com

The post 15 Wines You Must Try at the North Coast Wine & Food Festival appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

An environmental battle threatens the decades-old partnership between the National Park Service and ranchers at Point Reyes.

The post Point Reyes Ranchers: Point of Conflict appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

Photography by Kent Porter.

Storm clouds shadowed Ted McIsaac as he shifted his battered 1994 Chevy pickup into four-wheel drive and bounced along a muddy track over hills cloaked in brilliant green grass.

His border collie Rollin trotted alongside while McIsaac made a routine morning recon of his 2,500-acre Point Reyes ranch to scan the slopes near and far for his 160 head of pure black cattle. To the west, the dark spine of Inverness Ridge framed the horizon, and two miles beyond winter surf pounded a wild coastline.

“You rely on Mother Nature. She rules your day,” said McIsaac, 65, a lean, sturdy man with a creased face and square jaw. A fourth-generation rancher, he’s accustomed to the vagaries of weather, especially spring rains that can make or break a cattleman.

But a much larger storm now hangs over the remote Point Reyes peninsula, where a legal fight triggered by three environmental groups has profoundly unsettled life for McIsaac and the 23 other families who operate ranches on the federally protected landscape.

Theirs is a way of life often as rough as the relentless waves crashing at the edges of this timeless headland. And they believe the future of ranching is at stake in the 71,000-acre Point Reyes National Seashore, where pasture for beef and dairy cattle exists side by side with wilderness, both shielded from development in a unique preserve established by the federal government at the ranchers’ behest more than 50 years ago.

President John F. Kennedy, convinced it was some sort of charmed West Coast Cape Cod, created the national park after ranchers and environmentalists fearful of intense development pressures banded together to stop the encroachment of subdivisions on Point Reyes.

As part of the deal, the ranchers insist they were made a promise specifically designed to endure: They could remain as long their families were willing to work in the wet, cold and wind of an unforgiving landscape.

Point Reyes and its landscape are the center of an unfolding dispute that ultimately seeks to define the nature of the landscape in America’s national parks: Can the treasured public scenery accommodate the country’s ranching tradition?

The lawsuit, which has drawn wide attention to the region, does not directly seek removal of the ranches but raises fundamental questions about the purpose of the seashore. It claims that the ranching that began here more than 150 years ago — and continues under leases with the federal government — is harming the wildland and wildlife the park is also supposed to safeguard.

If studies show cattle are harming the seashore they could be prohibited, said Jeff Chanin, a San Francisco attorney who represents the plaintiffs. Federal court rules require the two sides to discuss a possible settlement that would avoid a trial, he said, and a conference is set for May.

The park, just an hour north of San Francisco, includes thick conifer forests, miles of unspoiled beaches, wetlands teeming with birds and coastal bluffs where herds of massive tule elk roam. About 2.5 million visitors, including hikers and backpackers, are drawn to the spectacle every year.

Over decades, thousands of grazing cattle have trampled that habitat and polluted those waterways, say the environmental groups that sued the National Park Service in February, saying none of the ranch leases, many on 1-year terms, should be renewed without further study of their impact.

“That’s a public landscape,” said Huey Johnson, a former California secretary of resources and founder of the Trust for Public Land. He now heads the Mill Valley-based Resource Renewal Institute — one of three parties that filed the lawsuit.

Johnson said the Park Service’s management of the ranches is a travesty.

“We’ve got pastures of mud and manure instead of wildflowers,” he said.

However, for the park’s ranchers and their many allies, who extend from West Marin to Capitol Hill, the lawsuit threatens not only a way of life but a nearly unprecedented experiment in the history of the national park system – the same network that includes beloved spots such as Yosemite and Yellowstone.

With the exception of an Ohio park, no other place in the country allows working ranches within national park boundaries.

The pivot by some environmentalists against ranches in the seashore threatens to undermine the foundational deal on which the park was established, said Rep. Jared Huffman, the whose North Coast district takes in the park.

He called the lawsuit a “frontal assault on any continued agriculture in the Point Reyes National Seashore.”

“We are not going to let these ranches and dairies go on my watch,” said the Marin County Democrat, a former environmental attorney.

Were it not for the lawsuit, this would be a pretty good season for Point Reyes ranchers. The wet winter and spring have delivered a plentiful grass crop to feed their herds and a respite from the worries of several drought-plagued years that nearly doomed some outfits.

In spring 2014, McIsaac came within 45 days of going broke after buying hay most of the year to feed his cattle. Late-March rains bailed him out.

“We raise cattle but what we really do is harvest grass,” he said.

McIsaac, who carries a cigarette pack in the pocket of his fleece vest, is the great-great-grandson of a Civil War veteran who came to the Point Reyes peninsula in 1865 as California’s dairy industry — now a $9 billion a year enterprise — was getting rooted in a lush landscape once described as “cow heaven.”

Home for his family is a pale-green, two-story farmhouse, part of it built in the 1880s, all of it crying for a coat of paint. One end of the house burned in 1955 and was upgraded, but since he sold the ranch to the government in 1983, McIsaac, like the other ranchers on short leases, has little ability to borrow money and gains no equity from making improvements.

Ranchers throughout the park are in the same boat, and few complain about it. Instead, they put greater stock in their ability to diversify and broaden their future agricultural options, adding other consumer products to bolster their finances.

As far back as the 1920s, Japanese farmers grew peas and Italians raised artichokes on what is now parkland next to Drakes Estero, the large tidal waterway at the heart of the seashore.

Fast-forward nearly a century and the larger region is renowned in the food world for its grass-fed beef and organic dairy goods, launching famed Bay Area labels such as Niman Ranch, the natural meat purveyor, and Cowgirl Creamery, the artisanal Point Reyes cheesemaker. But without 20-year leases, ranchers say, they are unable to borrow money to make the improvements needed to cash in on such trends in agriculture. Jarrod Mendoza, who milks about 200 cows on B Ranch near the tip of the Point Reyes peninsula, said he needs financing to rebuild an old wooden barn that blew down during a storm in March. “You don’t want to see the book closed,” said Mendoza, whose great-grandfather acquired the 1,200acre ranch in 1919.

The trio of environmental groups suing the Park Service, however, claim that a broader range of farming at the seashore ranches – including chicken, pig and row-crop production, for example – could result in more conflicts with wildlife and wilderness in the park.

Their lawsuit has targeted the renewal of ranching leases thathey fear could pave the way for broader agricultural operations.

That process, said Jeff Miller, of the Oakland-based Center for Biological Diversity, another of the plaintiffs in the case, is “predetermined”

to favor awarding the ranchers with the long-term leases they seek.

“It hasn’t asked whether ranch leasing is appropriate,” he said.

The suit, citing reports by the Park Service, contends that grazing cattle have polluted waterways such as Drakes Estero with manure and degraded the habitat of threatened or endangered species, such as coho salmon and California red-legged frog.

Ranchers bristle at claims their operations are damaging a land- scape their families have occupied for generations.

Nicolette Niman, who runs 175 cattle on a 1,000-acre ranch in Bolinas at the southern tip of the seashore, asserted in her book, “Defending Beef,” that small-scale, well-managed ranches are good for the land. Periodically moved from one pasture to another, cattle trim the grass, press seeds into the soil and fertilize it with their urine and manure, said Niman, who bills herself as “an environmental lawyer and vegetarian turned cattle rancher.”

“Human activity isn’t hostile to the principle of preserving the land,” she said. The prehistoric Coast Miwok maintained the peninsula’s coastal prairies by setting them on fire, and cattle grazing

continues that purpose, Niman said. An end to ranching would diminish the landscape and the community, Niman said.

“The beautiful, big, open areas you can walk through” would shrink under the advance of woodland, eliminating grasslands where hawks and eagles feed. Local schools, churches and businesses would lose the support of ranching families, who are “the bedrock of West Marin,” she said. “It would be transformative.”

Allies in the worlds of land conservation and academia have chimed in to support the ranchers’ place in the park.

“You can have wild spaces and agriculture side by side,” said Laura Watt, a Sonoma State University environmental historian whose 15- year study of the seashore has focused on the region as a working landscape, with human uses and wild habitats closely intertwined.

The opposite view, one held by the plaintiffs, Watt said, is an “absolutist” division of farm- and wildland that insists parks must minimize human presence to ensure “zero impacts” on the landscape.

The mix of ranching and wildland is “part of the charm at Point Reyes” and ought to be preserved, she said.

In the real world, ranchers and their allies are also worried what a smaller footprint in the park or constrained operations would mean for the future of North Bay agriculture. Prominent Marin County conservationist Phyllis Faber, who Co-founded the Marin Agricultural Land Trust, notes that the seashore ranchers were pioneers in open space-protection in 1960s when they agreed to sell their land to the government. Farm fortunes were waning at the time and the urban Bay Area was booming, putting immense pressure on peninsula landowners to sell out to developers.

But Faber, 88, now fears that move may turn out to be the “death knell” for the ranchers.

Congress could settle the matter, and possibly stifle future lawsuits, by reaffirming the place of ranching in the seashore. “It would save the ranchers a lot of heartache,” she said.

On a clear day, Rich Grossi and his wife, Jackie, can see the ocean from the picture window of their home on M Ranch — one of 14 historic “alphabet ranches” in the seashore.

When the fog rolls in, as it does about 200 days a year, visibility shrinks to a few feet and patrols of 1,200-acre spread become a bit dicey.

A visitor would call the setting spectacular, but Grossi, hardworking at 76, scans the terrain with a different eye, seeing ranch chores almost everywhere he looks. Fence repairs are endless.

“One night I lay in bed and tried to figure out how many gates we had,” he said. “I lost count.”

Still, the business is one the Grossis plan to pass down in their family. Their daughter, Diane Turner, lives in the house next door and represents the fourth generation on M Ranch.

“We’re growing food for people,” said Turner, 50. “Not like living in town. It’s a whole ’nother world.”

The Grossis admit to being rattled by the standoff over ranching in Point Reyes. It is the latest place where tough-minded environmentalists have called for greater scrutiny over livestock grazing on public lands in the western United States.

The Center for Biological Diversity, one of the more successful and well-known among those interests, specializes in lawsuits aimed at protecting endangered species. The group’s website touts that 93 percent of its cases “result in favorable outcomes.”

The third plaintiff involved in the Point Reyes suit, the Western Watersheds Project, includes among its litigation victories a 2007 federal court ruling that threw out rancher-friendly grazing regulations established by the George W. Bush administration on more than 160 million acres of public lands in 11 states.

“They’re not playing games,” said Mclsaac, who serves as president of the Point Reyes Seashore Ranchers Association. “That’s worrisome.”

Of particular concern for the ranchers and their allies is the Park Service’s shifting stance on the place of agriculture in the seashore. The worries were fueled by a bruising, 2-year battle the agency fought to close a popular oyster farm in the seashore in 2014. The case, which oyster farmer and Point Reyes rancher Kevin Lunny lost, went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

That case was different because Lunny purchased the property knowing his lease would expire. Still, it proved a searing, divisive experience for a West Marin community that prides itself on the value of both locally grown food and wild places.

Ranchers steer clear of faulting the Park Service, which is their landlord, but their allies question its commitment to agriculture. Lunny’s farm, they say, was railroaded out of the seashore after the agency became determined to end an 80-year history of oyster cultivation in 2,500-acre Drakes Estero.

In the case of the beef and dairy ranchers, Watt suggested the oyster war could predispose the Park Service to settle for “some kind of compromise” on leases rather than wage a long legal battle.

Nevertheless, the parks agency, even during that prolonged fight over the Drakes Bay Oyster Co., has sought to clarify that the seashore’s ranches are not in its sights and have a solid place in the park.

“Ranching is integral to our history and to our future here at Point Reyes National Seashore,” Park Superintendent Cicely Muldoon said in a press release in April 2014 at the start of a lengthy planning process. “For more than 50 years, ranchers and the park have been working together. This plan is an opportunity to build on that past, address current issues and strengthen our shared stewardship of these lands.”

The pact struck by ranchers years ago in the seashore’s formation ought to provide some reassurance that grazing and wilderness can continue to exist side by side, Muldoon said in an interview. “I don’t see it as a conflict at all at Point Reyes,” she said.

Environmental groups have succeeded before in removing cattle from a national park in California. A 1996 lawsuit by the National Parks Conservation Association culminated in a settlement that stopped grazing on Santa Rosa Island, which had become part of the Channel Islands National Park off the Santa Barbara County coast 10 years earlier.

The association, a group that acts as an environmental watchdog, parks lobbyist and sometime-litigant against the Park Service, said cattle grazing in that instance was harming the island’s ecology, along with a trophy-hunting operation.

The group also pushed aggressively for the ouster of the Drakes Bay Oyster Co., noting that the estero in which it operated was designated to become wilderness in 2012 when the farm’s 40-year permit was set to expire.

But in the current case, the group is backing agriculture in the ranch planning process.

“We support the combination of ranching and the seashore,” said Neal Desai of the National Parks Conservation Association. “We think that’s possible.”

Also supporting the ranchers is the powerful California Cattlemen’s Association, which represents the state’s $3 billion beef cattle industry.

The group has “butted heads plenty of times” with the Center for Biological Diversity in and out of court, said Kirk Wilbur, director of government affairs.

The latest lawsuit was no surprise, he said, in the wake of the oyster farm’s ouster. “It’s a pretty transparent attempt by radical environmental groups to get grazing off the landscape,” he said.

The plaintiffs insist that is not the goal of their lawsuit, calling such assertions “sensationalist.”

“There’s no call to an end to ranching in the litigation,” said Chance Cutrano of the Resource Renewal Institute, the group headed by Johnson, 83, the former state resources secretary and a widely respected figure in environmental circles.

Instead, the claimants want the Park Service to assess the impacts of ranching and devise a plan to address them, Cutrano said.

Whether ranching continues and what the conditions might be is “not up for us to decide,” he said.

For nature lovers savoring the spring wildflowers at Chimney Rock, panoramic views from Mount Vision and the stunning vista at 11-mile Point Reyes Beach, the national seashore offers the balm of wilderness. But those visitors, according to the Park Service’s own description, have “happened upon one of the earliest and largest examples of industrial-scale dairying in the state of California.”

Hikers heading to the four backcountry campgrounds feel they have found refuge from urban hubbub, but all of them are located on the site of vanished dairies. At Sky Camp, located near the summit of 1,407-foot Mount Wittenberg, large fir, cypress and eucalyptus trees mark the location of a dairy that milked 75 cows and made a ton of butter a month in 1901, according to local historian Dewey Livingston’s book, “Ranching on the Point Reyes Peninsula.”

When the national seashore was established in 1962, there were ranches and roads throughout the peninsula. Many have since been erased by the Park Service.

“The wilderness area is an artificially created and managed setting of pristine-ness, disregarding the actual history of the place,” Watt, the Sonoma State historian, said in a 2002 article.

Wild or not, it was a landscape and a way of living that called McIsaac back four decades ago, a few years after he’d bolted from the family ranch, convinced he never wanted to look at another milk cow.

He returned in 1975, working for his father, and he took over the ranch about 15 years later.

“I can’t imagine doing anything else,” he said, his stained work jeans and worn ball cap evidence of a long days spent outdoors.

The rhythms of daily life for McIsaac and fellow park ranchers are largely imposed by sunup-to-sundown chores and the harsh elements. Point Reyes is the second-foggiest place in North America, behind Grand Banks, Newfoundland, and the windiest spot on the Pacific Coast.

But beyond the weather, when ranchers find time these days to meet up, their talk inevitably turns to the lawsuit over their leases.

The discussion is filled with uncertainties, weightier even than those that usually dog them. Families with four and five generations of working the land worry that their dream of passing it on to their children and grandchildren won’t come to pass.

Rich Grossi, who has no plans to retire, said his family has put off talking about who will take over M Ranch when he does step back. “We’re kind of cooling it now to see if we’ve got a leg to stand on,” he said.

Settled in the comfortable ranch house kitchen, Jackie Grossi said the future is out of their hands.

“We don’t know where it’s going to lead,” she said. “It’s heartbreaking.”

The post Point Reyes Ranchers: Point of Conflict appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>