Some of these Sonoma County restaurants have been serving up epic meals for more than 100 years.

The post Historic Sonoma County Restaurants That Are Still Going Strong appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

In the restaurant business, it’s saying something to make it through the first year and rare to last more than 10. But in Sonoma County, there are more than a dozen restaurants that have survived well past their 30th year and a handful which have outlasted generations of diners, stretching back more than a century.

These are well-worn eateries that have a proven formula. Most share a common heritage: They were built by Italian immigrants and have continued to serve hearty family-style meals at approachable prices for decades. It’s not a stretch to say that the farms, timber mills, railroads and vineyards of Sonoma County were built on pasta and meatballs. And maybe a steak or two.

We pay homage to several tried and true local restaurants that have stood the test of time and are still going strong.

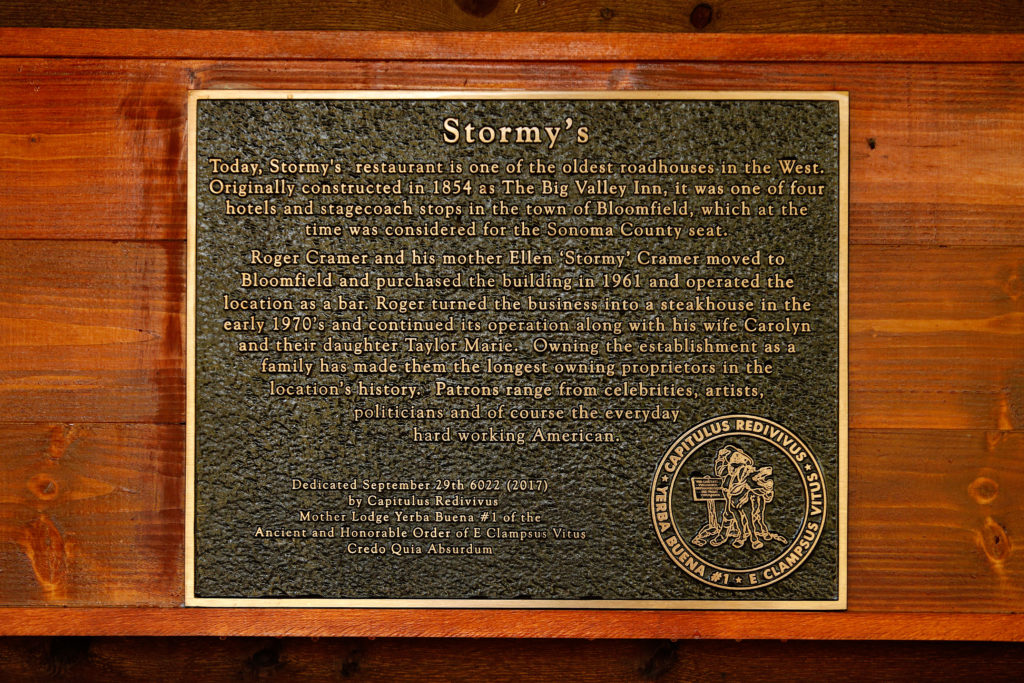

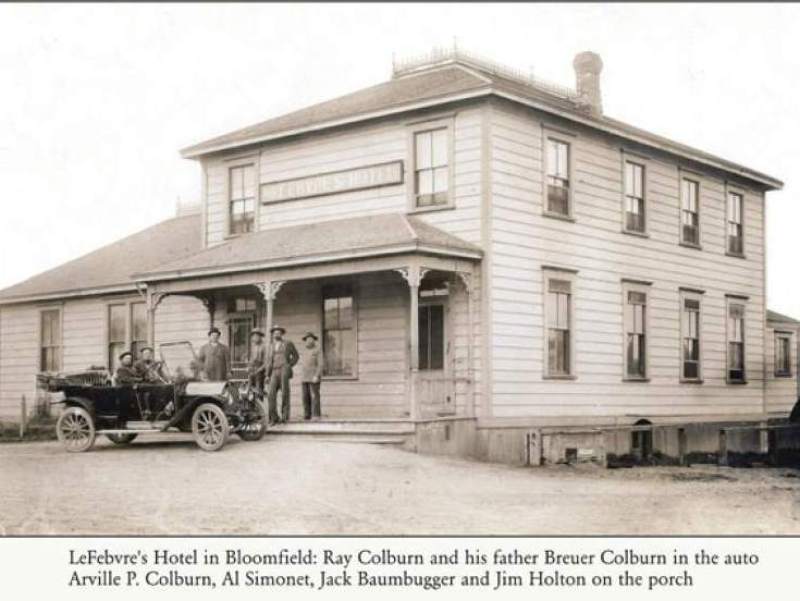

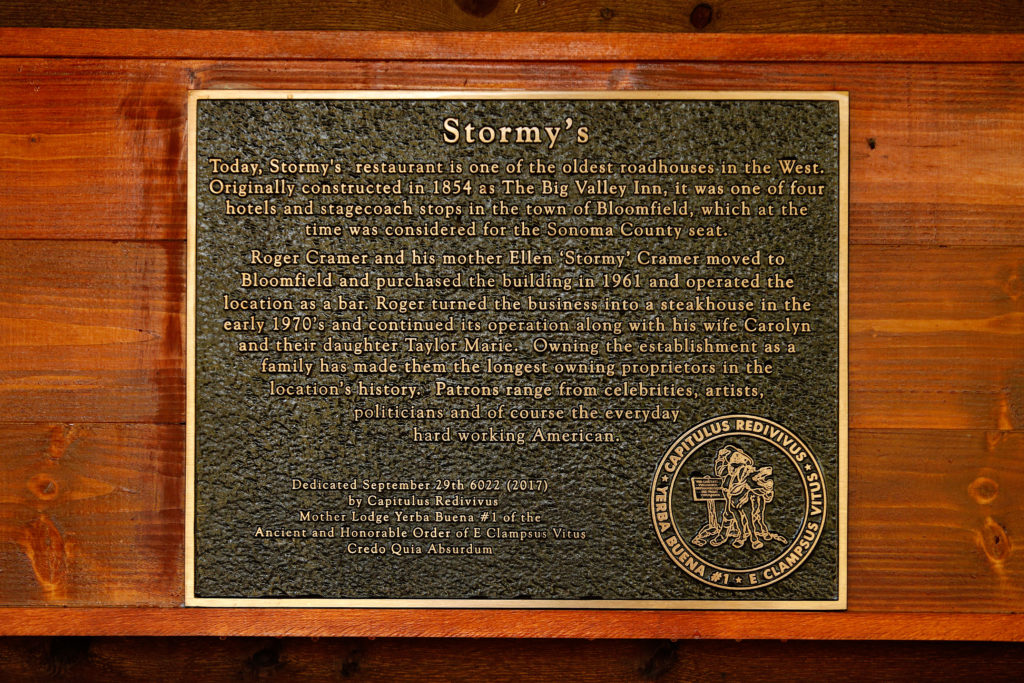

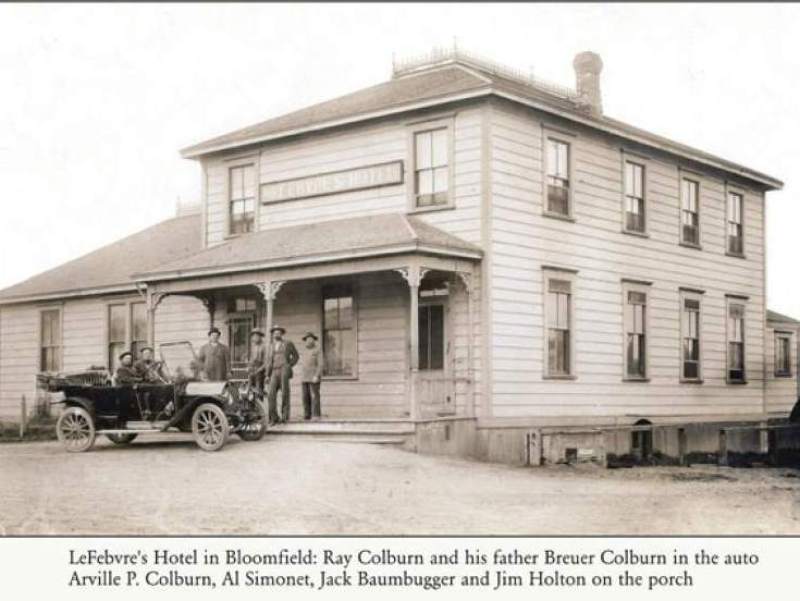

Stormy’s Spirits and Supper, 1854

Established as a roadhouse, Stormy’s has hosted generations of Sonoma County diners. The restaurant turned into a steakhouse in the early 1970s and remains a family-style dining destination in Bloomfield. Open limited hours Friday through Sunday. Call or check Stormy’s Facebook page for updates. 6650 Bloomfield Road, Petaluma, 707-795-0127, stormysrestaurant.com

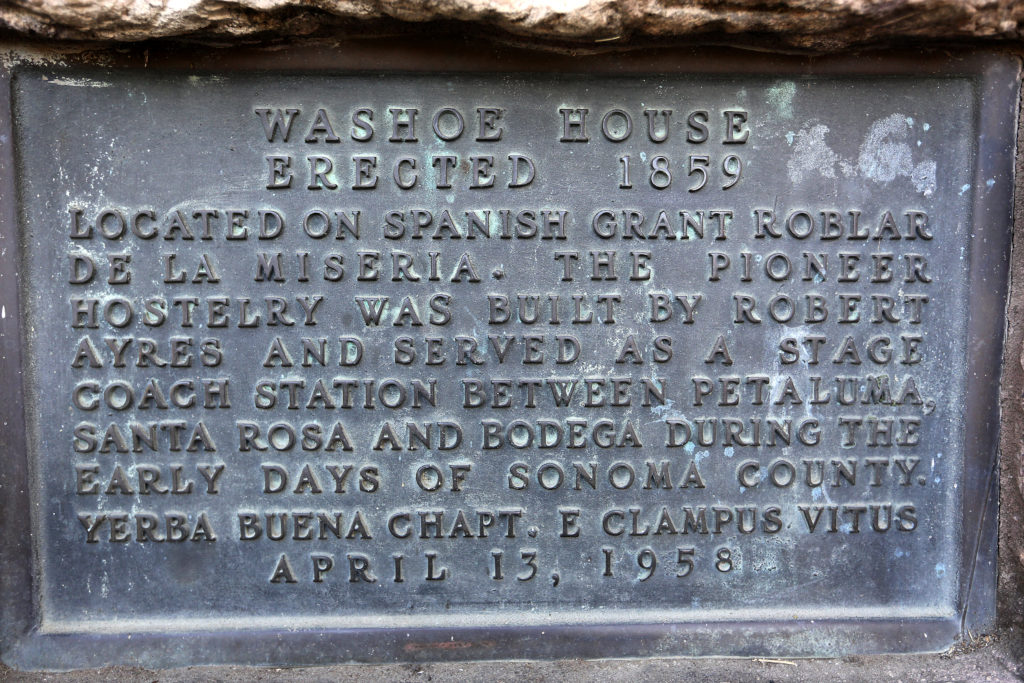

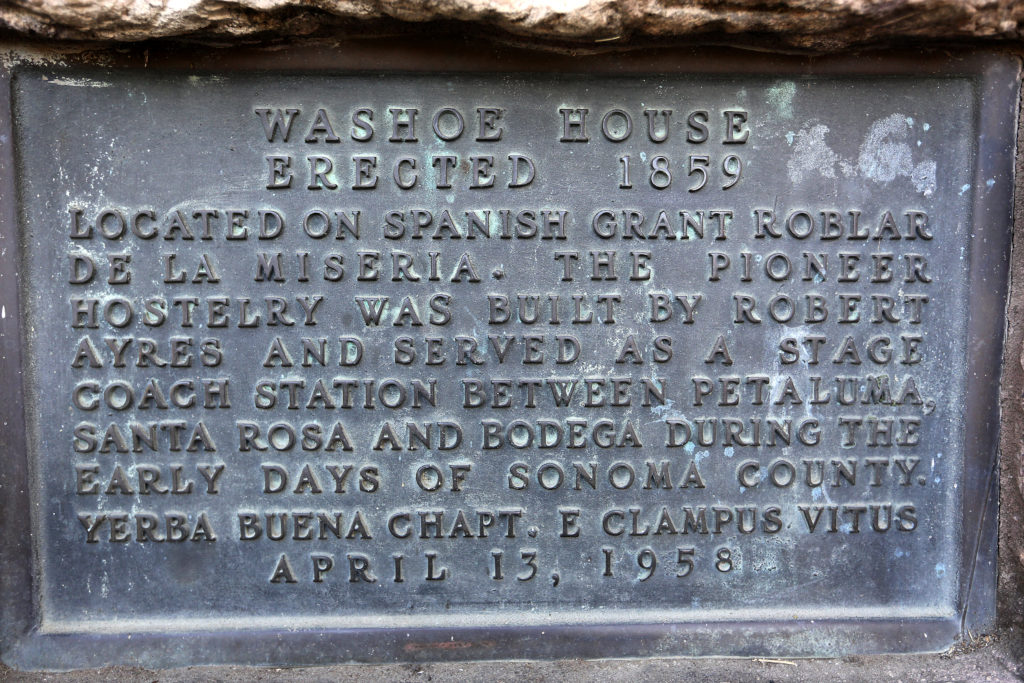

Washoe House, 1859

A former stagecoach stop connecting Petaluma, Santa Rosa and Bodega, this historic roadhouse is best known for two things: Dollar bills pinned to the bar ceiling and The Battle of the Washoe House. According to legend, following the 1865 assassination of president Abraham Lincoln, a group of Petaluma militia were intent on creating trouble for Southern-leaning Santa Rosans. Their thirst got the best of them and the group ended up getting drunk instead of rabble-rousing. 2840 Roblar Road, Petaluma, 707-795-4544, washoehouse.site

Union Hotel, 1879

This Occidental restaurant has been around for 146 years. What began as the Union Saloon and General Store grew into a family business, with four generations managing the restaurant over the years. The restaurant serves salads and pizza as well as a fan-favorite bruschetta. Open 4-8 p.m. Friday and noon to 8 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. (Note: The Union Hotel in Santa Rosa has separate ownership and is open daily.) 3731 Main St., Occidental, 707-874-3555, unionhoteloccidental.com.

Madrona Manor, 1881

The historic hotel underwent a major renovation in 2022, reopening as The Madrona. While the property has retained its Victorian past, the restaurant, mansion and guest houses have been infused with a modern, artistic sensibility. Chef Patrick Tafoya oversees the restaurant, offering an upscale dinner menu, relaxed lounge dining and a popular brunch. 1001 Westside Road, Healdsburg, 433-4321, madronamanor.com

Swiss Hotel, 1892

Sonoma’s history is etched into the walls of this historic inn, restaurant and bar. An Italian-focused menu reflects the generations of family ownership. 18 W. Spain St., Sonoma, 707-938-2884, swisshotelsonoma.com

Pick’s Drive In, 1923

One of the oldest hamburger joints in America, this Cloverdale drive-in has been serving up beefy burgers, hot dogs and shakes for over a century. The restaurant sources local produce and meat for its menu, and offers hand-scooped shakes, malts and soft serve with a modern twist. The historic drive-in is currently closed, but new ownership and upcoming renovations were announced in June. 117 S. Cloverdale Blvd., Cloverdale

Volpi’s Ristorante & Bar, 1925

Though it has operated as a grocery for most of its existence, Volpi’s major claim to fame was as a Prohibition-era speakeasy. Locals know that the “secret” bar is still in operation, with a convenient escape door to the alley in case of a raid. Or your ex-wife. The grocery became a full-fledged restaurant in 1992, though there’s still an old Italian grocery vibe with well-worn wooden floors and walls lined with Italian tchotchkes, accordions and candle wax-covered Chianti bottles. 124 Washington St., Petaluma, 707-762-2371, volpisristorante.com

Catelli’s, 1936

Italian immigrants Santi and Virginia Catelli opened Catelli’s “The Rex” in tiny Geyserville as a humble family eatery, serving up spaghetti, minestrone and ravioli. After closing in 1986, the restaurant later reopened in Healdsburg, where it stood until 2004. In 2010, siblings Domenica and Nick Catelli reopened Catelli’s at the original Geyserville location, where it has been host to a number of celebrities, but remains an approachable family-style restaurant. Their paper-thin layers of lasagna noodles make Catelli’s version one of the best in the region. 21047 Geyserville Ave., Geyserville, 707-857-7142, mycatellis.com

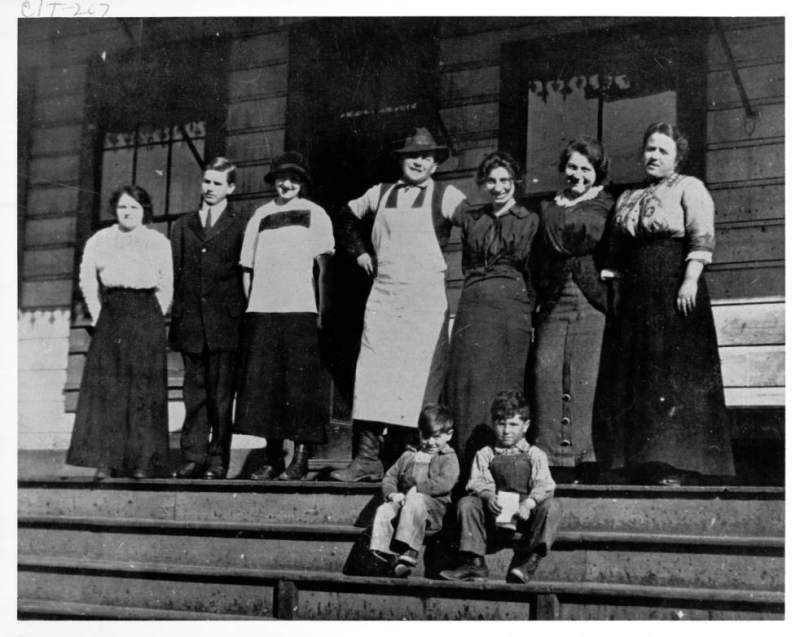

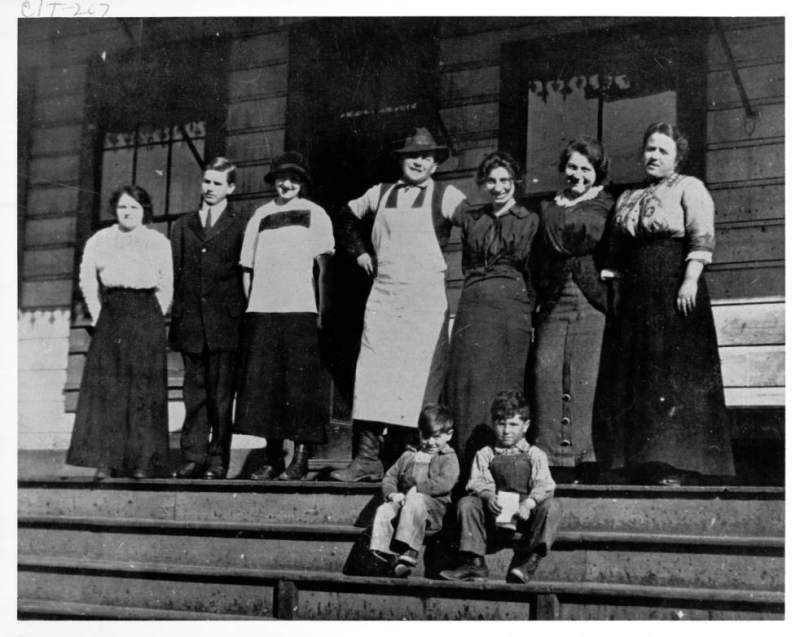

Dinucci’s Italian Dinners, 1939

Though the building dates back to 1908, when it served train travelers, the current restaurant didn’t open until 1939. Owners Henry and Mabel Dinucci turned it into a welcome stop for hearty family-style Italian dinners. In 1968, Dinucci’s sold to the Wagner family, but some of Mabel’s original recipes are still in use today. The historic interior hasn’t changed much over the years, with red-and-white checkered tablecloths right out of the 1940s. 14485 Hwy. 1, Valley Ford, 707-876-3260, dinuccisrestaurantandbar.com

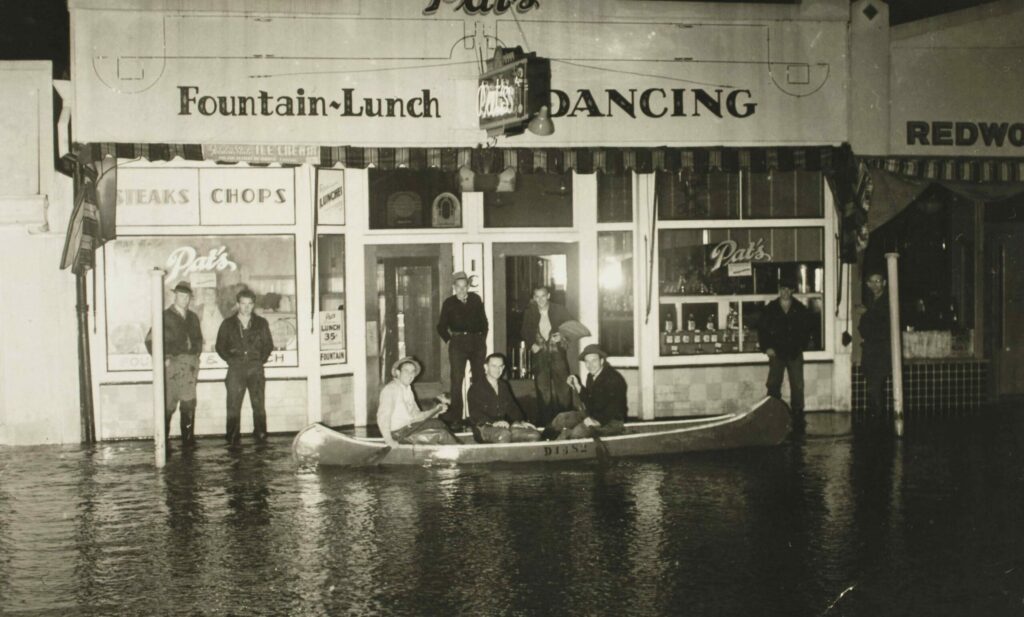

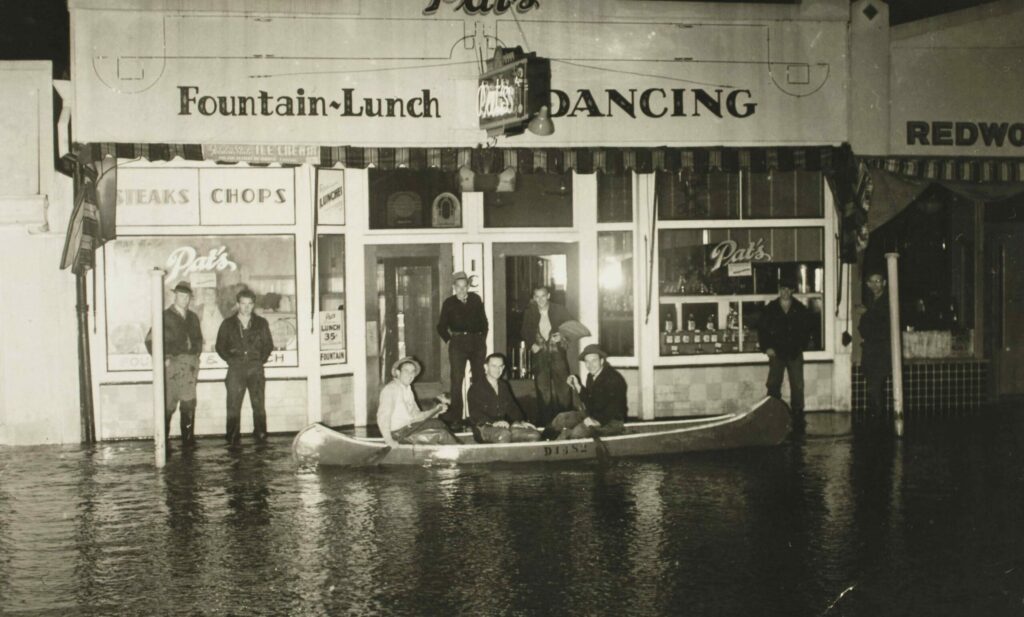

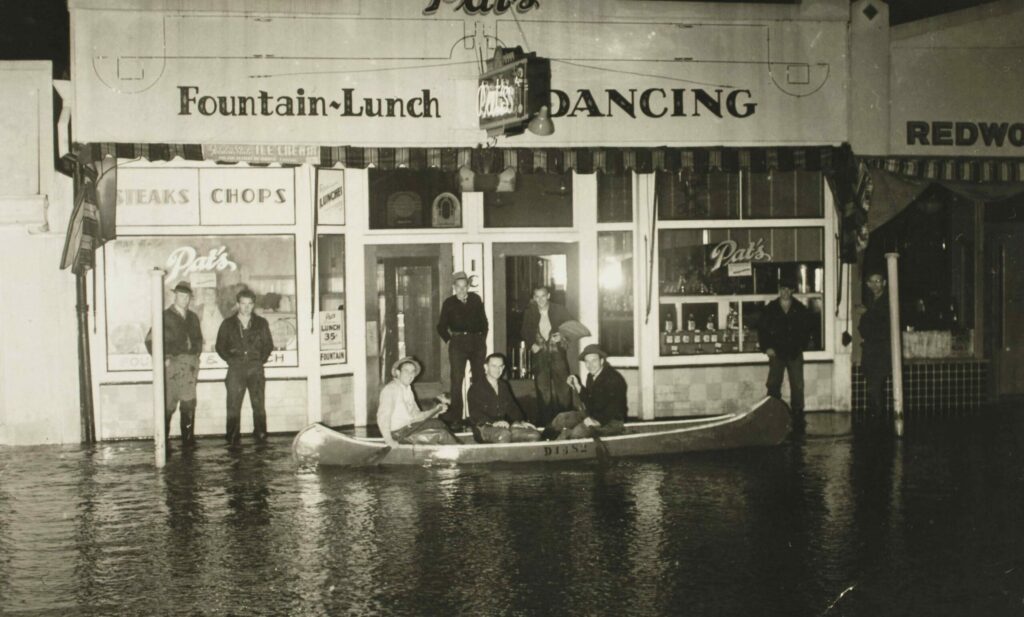

Pat’s International, 1940

Pat’s in Guerneville has been a reliable Russian River eatery for over 80 years, weathering everything from floods to global pandemics. Late last year, owner David Blomster put the business up for sale, however, the restaurant continues to serve customers. 16236 Main St., Guerneville, 707-604-4007, patsinternational.com

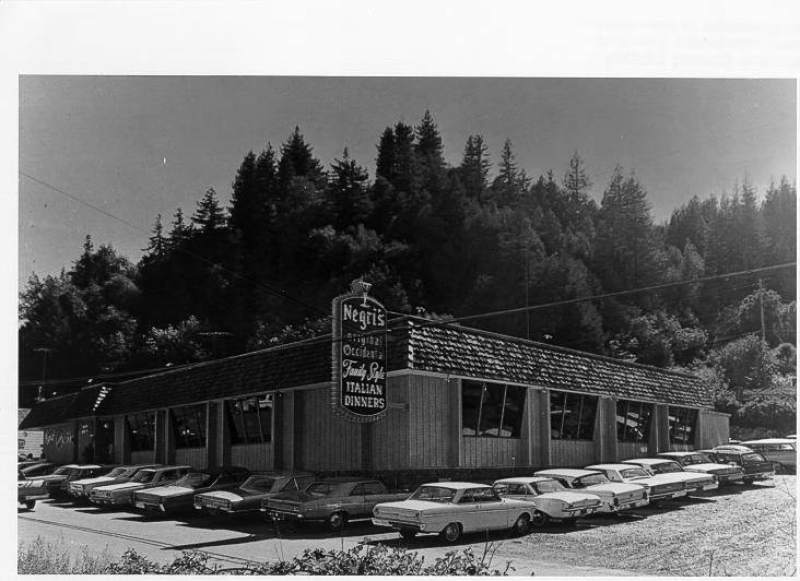

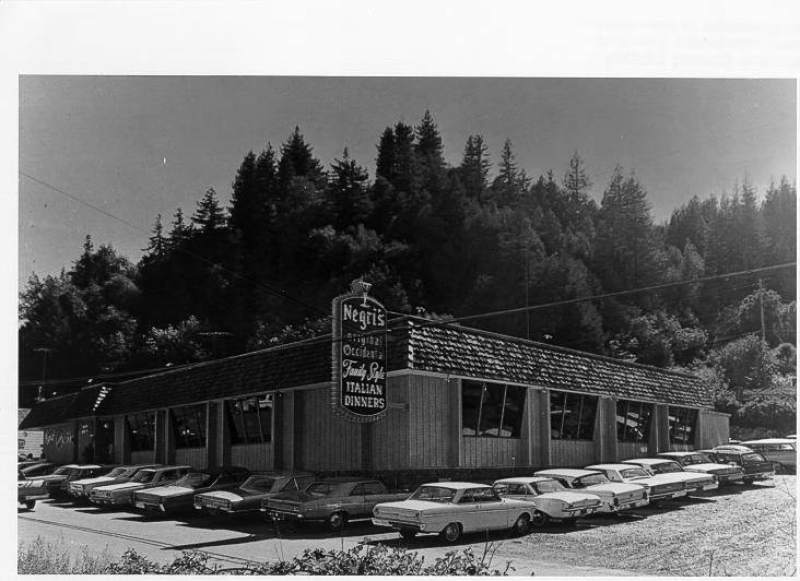

Negri’s, 1942

This family-owned Italian restaurant began as a stopover for train travelers journeying from San Francisco to Eureka. According to restaurant lore, original owner Joe Negri Sr., an Italian immigrant, was once the personal chef for movie legend Rudolph Valentino. After moving to Santa Rosa, he opened Negri’s, which has served traditional Italian pasta dinners ever since, many made using original recipes from the 1930s. Open for dining in the attached Joe’s Bar from 4-8 p.m. Friday and Saturday and 3-8 p.m. Sunday, offering its famous ravioli, burgers, pizza, salads, sandwiches and housemade desserts. 3700 Bohemian Highway, Occidental, 707-823-5301, negrisrestaurant.com

Superburger, early 1950s

Opened as a modest burger shack on the corner of Santa Rosa’s College and Fourth streets in the early 1950s, Superburger has become one of Sonoma County’s go-to family spots for made-to-order char-grilled hamburgers, tater tots, onion rings and old-fashioned milkshakes. Two locations: 1501 Fourth St., Santa Rosa, 707-546-4016, and 8204 Old Redwood Highway, Cotati, 707-665-9790. originalsuperburger.com

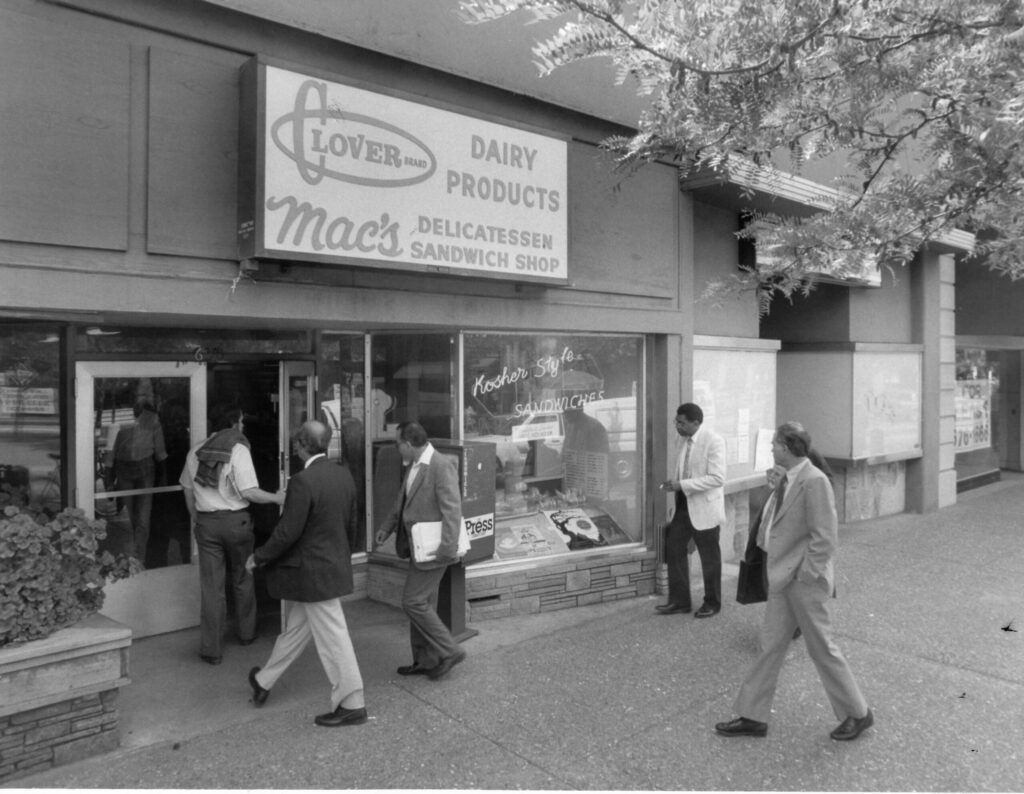

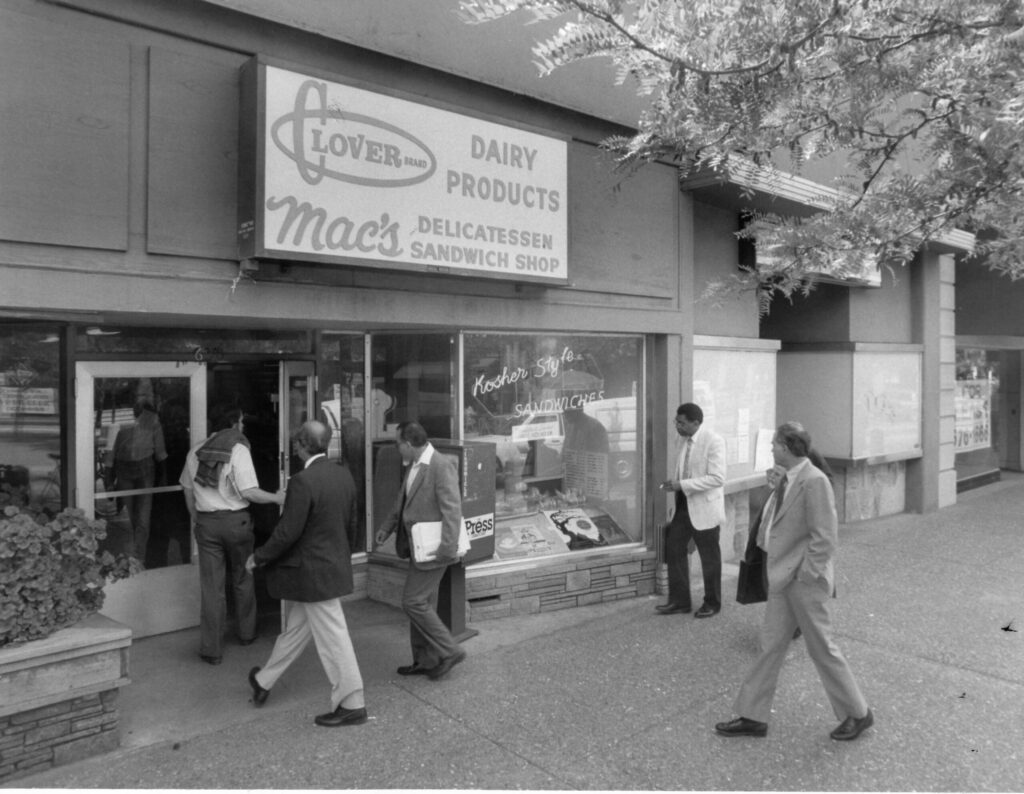

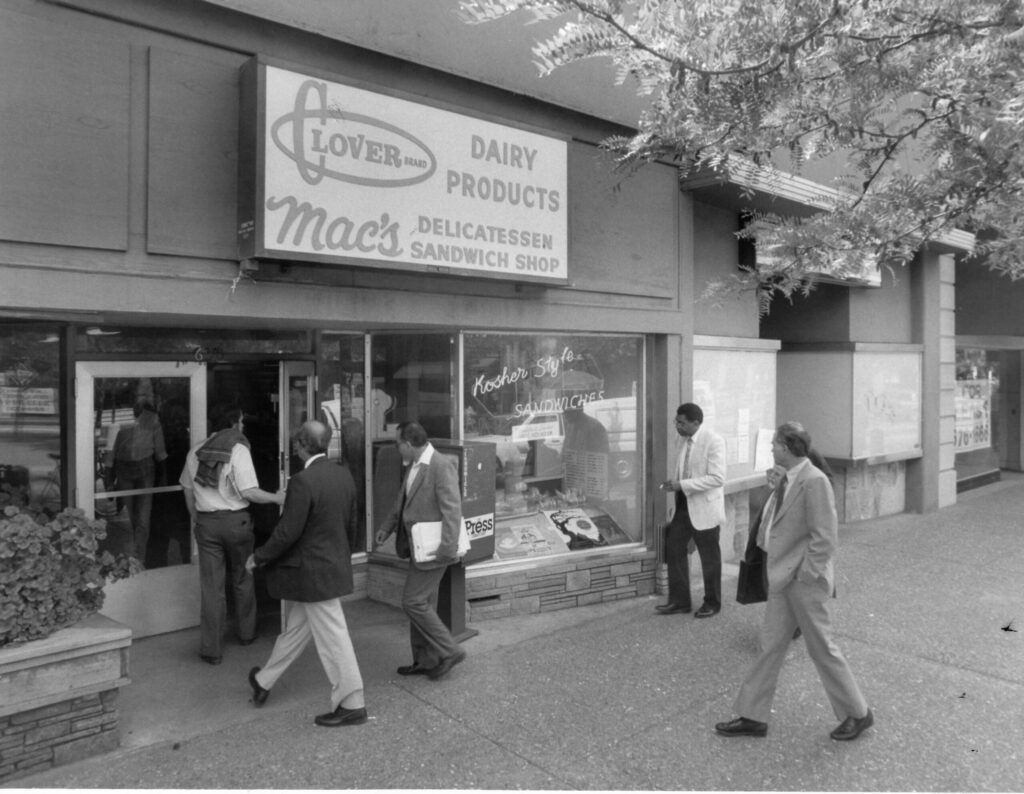

Mac’s Deli, 1952

Mac’s bills itself as Sonoma County’s oldest continuously operating breakfast and sandwich café. Opened by Mac Nesmon in 1952 as a New York-style deli, it was purchased in 1970 by the Soltani family, who still run the restaurant today. Don’t miss the classic Reuben sandwich. 630 Fourth St., Santa Rosa, 707-545-3785, macsdeliandcafe.com

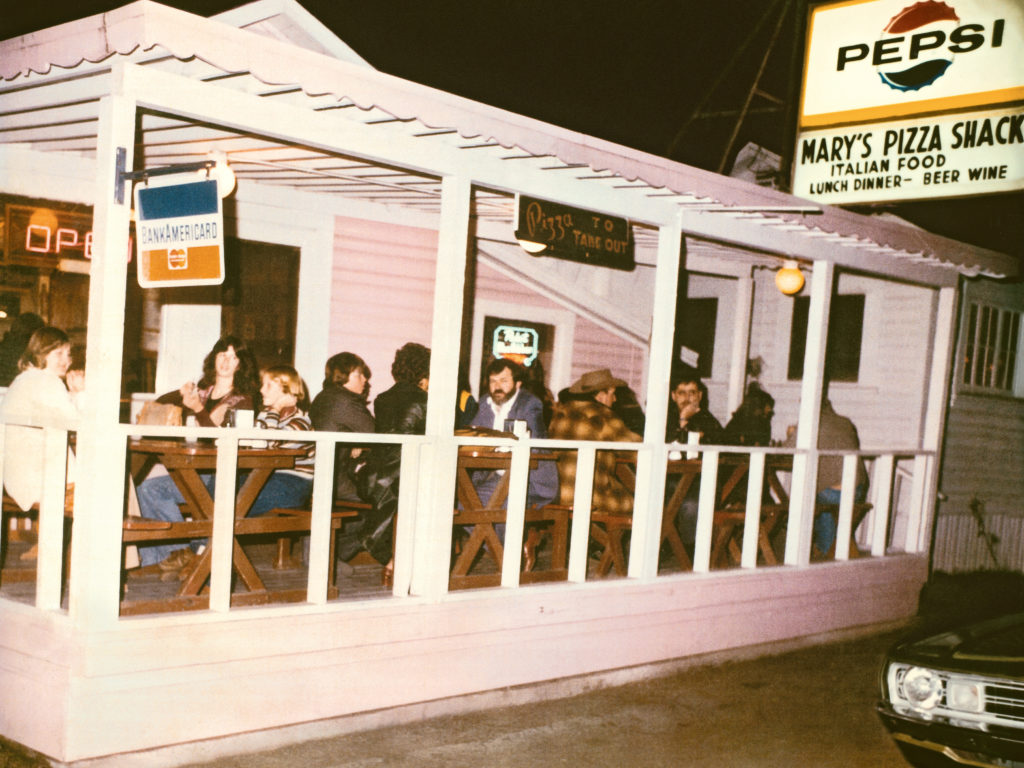

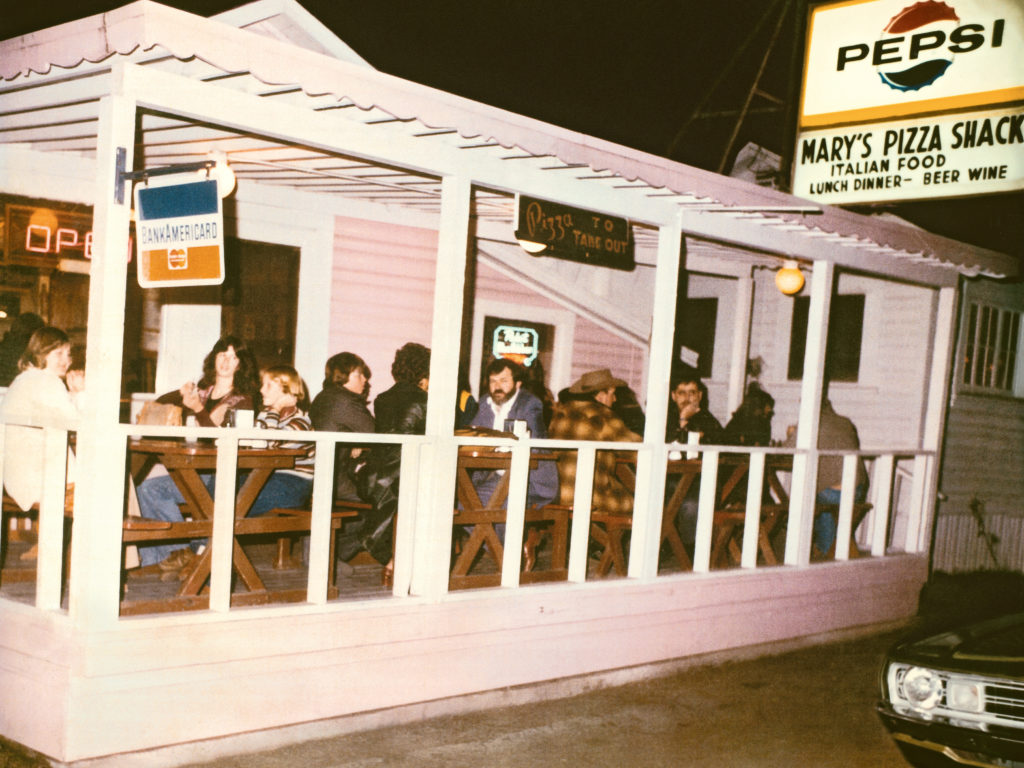

Mary’s Pizza Shack, 1959

Mary Fazio opened her first pizzeria in Boyes Hot Springs in 1959 using family recipes and her own pots and pans. Thought Fazio died in 1999, her legacy lives on in the family-owned restaurant chain with locations across the North Bay. maryspizzashack.com

Tide’s Wharf, around in different shapes and forms since the 1950s

Made popular by Alfred Hitchcock’s 1963 thriller “The Birds,” this Bodega seafood restaurant has been a coastal staple for more than 50 years. With sweeping bay views, it remains a magical spot. 835 Bay Highway, Bodega Bay, 707-875-3652, innatthetides.com/tides-wharf-restaurant

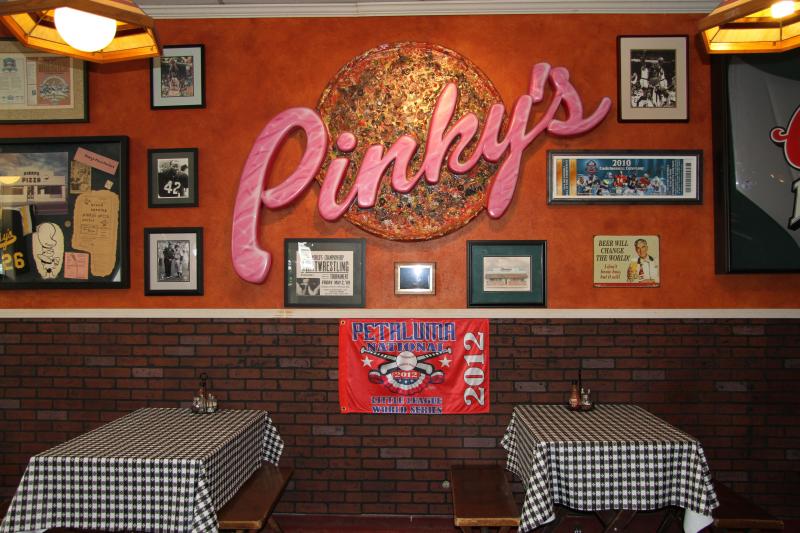

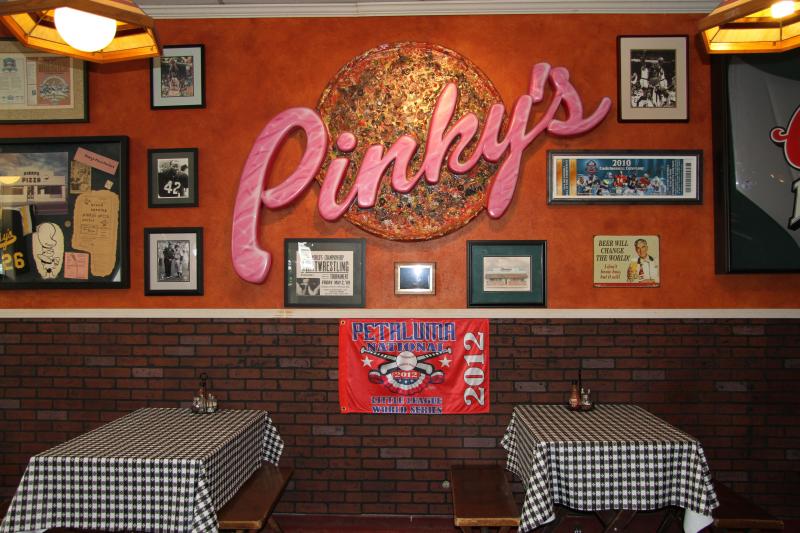

Pinky’s Pizza, 1962

A classic hometown pizza parlor, loved by generations of Petalumans. 321 Petaluma Blvd. South, Petaluma, 707-763-2510, facebook.com/pinkyspizzapetaluma

La Casa, 1967

Opened in the late 1960s, La Casa has seen Sonoma’s transformation from sleepy rural town to bustling tourist destination. The restaurant was purchased in 2015 by the Sherpa Brothers Group, Nepalese restaurateurs who’ve revitalized several local restaurants. La Casa continues to serve simple, traditional Mexican cuisine — if you go, don’t miss the margaritas. 121 East Spain St., Sonoma, 996-3406, lacasarestaurants.com

Betty’s Fish and Chips, 1967

Serving English-style fish and chips and the world’s best lemon pie, Betty’s has been a Santa Rosa favorite for over five decades. The restaurant got a face-lift in 1996 but remains true to its roots. 4046 Sonoma Highway, Santa Rosa, 707-539-0899, bettysfishandchips.com

Costeaux French Bakery, 1973

In 1973, French natives Jean and Anne Costeaux bought a 1920s-era French American bakery in Healdsburg and renamed it Costeaux French Bakery. Karl and Nancy Seppi purchased the bakery in 1981 with a vision to expand — and Jean taught them the art of bread baking. Today, Costeaux, with additional locations in Santa Rosa and Petaluma, is renowned for its sourdough baguettes, French macrons, princess cake and cinnamon walnut bread. 417 Healdsburg Ave., Healdsburg, 707-433-1913, costeaux.com

Blue Heron, 1977

The building that houses Blue Heron was originally built in the late 1800s, but the 1906 earthquake destroyed most of Duncans Mills. In 1976, a restoration project revived the town — and with it, the Blue Heron. The restaurant’s expansive menu includes local seafood, burgers, salad and chowder. 25275 Steelhead Blvd., Duncans Mills, 707- 865-2261, blueheronrestaurant.com

Don Taylor’s Omelette Express, 1977

Most weekends, Don Taylor can be found at the door of the original Omelette Express in Santa Rosa, greeting regulars who have made a breakfast at his restaurant a family tradition. Opened in 1977, the all-day breakfast spot has since expanded to Windsor and, in 2018, it went international with a location in JeJu City, South Korea — Santa Rosa’s sister city. Omelets remain a best bet, of course, but there’s plenty more to explore on the menu, including Benedicts, burgers, sandwiches and salads, plus some of the best coffee in town. 112 Fourth St., Santa Rosa, 707-525-1690; 150 Windsor River Road, Windsor, 707-838-6920, omeletteexpress.com

Old Chicago Pizza, 1978

Opened by William Berliner in 1978 inside a historic 1870s building, Old Chicago Pizza has become a Petaluma fixture, known for its hearty, deep-dish pies served in a space that reflects the city’s historic charm and offers a second-floor view. 41 Petaluma Blvd. North, Petaluma, 707-763-3897, oldchgo.com

La Gare, 1979

Chef Roger Praplan relishes the fact that he’s now serving the grandchildren of some of La Gare’s early customers. His parents, Swiss-born Marco and Gladys Parplan, opened the restaurant in 1979 after purchasing the lot for $25,000 two years earlier. Though dining trends have come and gone since, La Gare has remained steadfast in its approach and was featured on KQED’s “Check, Please! Bay Area” last year for staying “true to its Swiss-French roots.” 208 Wilson St., Santa Rosa, 707-528-4355, lagarerestaurant.com

John Ash & Co., 1980

Long before “farm-to-table” became a culinary catchphrase, John Ash was sourcing local produce, dairy and meat for wholesome, seasonal dishes paired with excellent regional wines. His namesake restaurant helped define Sonoma County’s food identity and launched the careers of many local chefs and winemakers, including Jeffrey Madura, Dan Kosta and Michael Browne. Though Ash has stepped away from the restaurant kitchen, John Ash & Co remains a top dining destination with a recently revamped menu following the renovation of Vintners Resort (where the restaurant is located), now named Vinarosa. 4330 Barnes Road, Santa Rosa, 707-527-7687, vinrosaresort.com

Grateful Bagel, 1981

Founded by East Coast transplants yearning for New York-style bagels, Grateful Bagel opened in 1981 on Mendocino Avenue in Santa Rosa. Within a year, the bakery was distributing its bagels to delis and grocery stores from San Francisco to Fort Bragg. While the original location has since closed, Grateful Bagel locations can be found at 631 Fourth St. and 925 Corporate Center Parkway in Santa Rosa; 300 South Main St. in Sebastopol; 221 N. McDowell Blvd. in Petaluma; and 10101 Main St., Suite A, in Penngrove.

Worth the trip: Tony’s Seafood Restaurant, 1948

For nearly seven decades, this seafood shack overlooking Tomales Bay was run by a Croatian fishing family. By the time it changed hands in 2017, it was a fading relic, but a two-year renovation by the owners of Hog Island Oyster Co. brought new life to the space. Today, Tony’s is a vibrant, modern seafood house with panoramic bay views. 18863 Shoreline Highway, Marshall, 415-663-1107, tonysseafoodrestaurant.com

The post Historic Sonoma County Restaurants That Are Still Going Strong appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

A century after his death, Jack London's legacy still thrives.

The post The Times of Jack London appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>

She spent just 13 years with Jack London, yet the wife of one of America’s most beloved writers, bravest adventurers, earliest environmentalists and infatuated lover of Sonoma Valley, devoted nearly 40 years, until her death in 1955, to protecting and polishing his legacy. This year marks a century since London’s 1916 death, at the young age of 40, and Charmian London would likely be pleased that so much of his Glen Ellen ranch, his accomplishments and his memory have been maintained.

“Mate-Woman,” as London called her, spent decades tending to his copyrights and writings, a prolific output of more than 50 works of fiction and nonfiction, and hundreds of short stories, essays, newspaper and magazine articles, speeches and letters, translated into as many as 70 languages. And with London’s stepsister, Eliza Shepard, she struggled, sometimes mightily, through the Depression and World War II to pre- serve the mountainside he venerated and keep his Beauty Ranch going.

“Jack London loved Sonoma and in an important way, he was one of the first people to put Sonoma on the map and in the international imagination,” said former state librarian Kevin Starr, author of the book series “Americans and the California Dream.” “He sought the redemptive life on the land in Glen Ellen and as a rancher. Collectively, within the 50-plus books he wrote, are guide maps of Sonoma places that later became famous.”

This is a watershed year for Jack London State Historic Park, which occupies a portion of the original Beauty Ranch. The Jack London Park Partners group plans to spend 2016 celebrating London’s enduring legacy. Special events and activities kick off with the Klondike Challenge, encouraging people to pledge to walk 500 miles throughout the year, the distance London hiked from the Yukon to the Klondike in Canada. The kickoff coincides with London’s 140th birthday on Jan. 12. The commemorative year culminates with a memorial at his grave site, on the centennial of his death, Nov. 22. Fittingly, London died on his ranch and is buried there.

To honor her husband, Charmian London built a sturdy stone lodge, the House of Happy Walls, a smaller version of the magnificent Wolf House that mysteriously burned to the ground on a hot August night in 1913, two weeks before the couple were to have moved in. Like Wolf House, Happy Walls was designed by eminent Bay Area architect Albert Farr, to eventually serve as a Jack London museum; the first public visitors streamed under the portico in 1960, finally fulfilling Charmian’s wishes; nearly 100,000 people a year now come to Jack London State Historic Park, and he is remembered by readers around the world.

As a writer, London’s creative fire was stoked by social revolution. Far more than a manly writer of popular adventure stories such as “The Call of the Wild” (1903) and “White Fang” (1906), he also exposed the plight of the underclass and the working poor. His dystopian “The Iron Heel” described the rise of a tyrannical oligarchy that some observers find relevant today. He dressed in rags and lived among the destitute in the streets of London’s East End to research “The People of the Abyss.” His unfettered range took in everything from astral projection to prize fighting to penal reform.

London scholar Earle Labor, an emeritus professor at Centenary College in Louisiana and author of the recently published “Jack London: An American Life,” recalled meeting a young man from the Congo at a seminar. The man confided that his father had been killed in a jungle village, yet the son later learned to read French and discovered “The Call of the Wild,” which has been in continuous print since it was published in 1903. The story of Buck, a tenacious sled dog, inspired the young man’s own survival.

On a recent day in the state park, Tony Holroyde, visiting from England, paused on the porch outside London’s restored cottage and reflected that the rugged American writer lit a fire under him when he was a youth.

“He brought adventure alive in my imagination,” he said. “I don’t think I otherwise would have left the U.K. and spent two years running around the world. But I didn’t do it on horseback and I didn’t do it on a leaky ship.”

And yet in the last years of his short life, the 1,000 words a day London claimed to produce were largely in service to his 1,400 acres overlooking what he romantically referred to as the Valley of the Moon. The most highly-paid writer of his day, London pumped out the prose to pay for Beauty Ranch, his “biggest dream,” which started out as a refuge from urban grime and became a grand experiment in sustainable agriculture. Ridiculed in his time, he’s now regarded by many as a visionary.

Mike Benziger, who planted his family vineyard within the same well drained volcanic soil nearby on the mountain, said London was struck by the overgrazed and degraded condition of the Hill Ranch when he purchased the first 130 acres in 1905 and set out to make “the dead soil live again.”

“He felt he was in a position to save it. That was his life-altering experience the day he set foot on Beauty Ranch,” Benziger said. “That became literally this mission for the rest of his life, to find respite in this place and make it healthier and make it an example for future generations.”

Credit for London’s enduring legacy goes to the early efforts of his widow and several generations of heirs, including members of the Shepard family, who inherited the ranch from Charmian and made most of it available to the state for parkland, and the offspring of Jack London’s two daughters, Joan and Becky, many of whom carry on his commitment to social equality and justice in their own ways.

But London’s spirit has also been taken up by a multitude of other acolytes and academics who approach him from a kaleidoscope of perspectives. They include literary scholars, historians, agriculturists, preservationists, naturalists, teachers and outdoor enthusiasts who roam the 26 miles of trails that crisscross what is now Jack London State Historic Park.

“He wrote books kids used to read and still have to read. That’s how many people get exposed to Jack London, and it’s pretty much all most people know about him. He wrote dog books,” said Chuck Levine, a director of Jack London Park Partners, which has greatly expanded the park’s visibility and use since taking over management three years ago after the state threatened to close it due to budget constraints.

“The reason we should care about Jack London is that he was deeply concerned about the human condition,” Levine continued. “And the fact he was a writer allowed him to express that concern and his views about how the world could be changed to help the state of mankind.”

A meadow and a screen of trees but no fencing separate his property from the park. He lives on a piece of land sold off decades ago to help keep the ranch going. Levine crosses over almost daily. Since moving to Glen Ellen in 2002, the former CEO of Sprint has spent more than 300 hours exploring the park on horseback, just as London did a century earlier. He declares himself a pragmatist but admits, almost apologetically, that when he first crossed a wooden bridge onto what was once London’s land, “In my heart it felt magical.”

Levine is typical of the passionate volunteers who lead nature and historic hikes, give tours, work in the cottage and Happy Walls museum, patrol and maintain the trails, help with special events and man the parking kiosk.

At the same time, the partners are launching a $1 million capital campaign to modernize the museum in the House of Happy Walls with more high tech and multimedia presentations; the exhibit has changed little in decades.

If London were to return today, he would have no trouble finding his way around Beauty Ranch and the park. Aside from the 160 acres that London’s heirs, the Shepards, held back in a family trust when they turned the remainder of the property over to the state in the late 1970s, it has remained largely the same for over 100 years.

Some 700 feet up the slope of Sonoma Mountain, the ranch still has the old fieldstone barns, the elaborate piggery dubbed the Pig Palace by scornful observers, the concrete-block silos that were cutting-edge at the time, the picturesque ruins of the Kohler and Frohling winery destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and now the backdrop for the Transcendence Theater Co., and the mid-19th century cottage where Jack lived with Charmian and wrote in a study outfitted with a Dictaphone, Gramophone and Remington typewriter — high-tech at the time.

Above the working farm is wild land thick with oaks, broad-leaf maples, manzanitas and madrones, as well as Douglas fir and redwoods — the eldest a sapling at the birth of Christ. The mountain is etched with canyons and creeks, and the year-round Graham Creek (Wild Water Creek in London’s day) is a spawning ground for steelhead trout. High meadows break out with golden poppies in spring and offer unbroken views of Sonoma Valley and beyond. Bobcats, mountain lions, gray foxes, hawks and falcons scour the mountainside for prey.

At the center of any mention of London is his larger-than-life persona that makes him a magnetic character even now. He was a dashing man’s man with a face for the camera, and courted danger in exotic places, from the Klondike to the South Seas. He was, among many things, a prospector, oyster poacher, seaman and hobo riding the rails to Washington, D.C., as an idealistic member of the Industrial Army of the Unemployed in the 1890s.

“The greatest story Jack London ever wrote was the story he lived,” said Matt Atkinson, who led tours for years as a ranger at the state park. He is now the fire chief of Glen Ellen, where the name of its favorite son carries on with a hotel, saloon and rustic retail center across from what for years was the World of Jack London Bookstore; it’s now a wine tasting room.

London crammed far more living into 40 years, said Atkinson, than most people would or could in 80 years.

At the same time, he was a bundle of contradictions. His writing ran from pedantic to brilliant. He was a Socialist who was partially raised by an African American wet nurse, yet many of his most memorable characters are rugged individualists. Threaded through his writings are racist tones that make the modern reader wince. He was the highest-paid writer of his day, the first to earn $1 million, which he spent as fast as he made it. He lived well while serving as a voice of the proletariat, and like John F. Kennedy, projected a charismatic virility, yet privately suffered from health problems exacerbated by a reckless lifestyle of hard-drinking, smoking and a poor diet. It all caught up with him at 40.

In his day, London was an international celebrity, as famous as a movie star. His death of reported uremic poisoning brought on by kidney failure — still a subject of speculation and debate along with the burning of Wolf House — rated front-page notice in the New York Times.

As one journalist wrote in the days after his death, “No writer, unless it were Mark Twain, had a more romantic life than Jack London.”

“I like to say that if Jack London were alive today he would probably have a reality show, because he really organized his life that way. He knew the value of publicity. Once he became a famous writer and had developed a persona, he exploited that persona for all it was worth, and in particular, to help boost his book sales,” said Bay Area filmmaker Chris Mullion, who is working on a documentary called “Jack London, 20th Century Man.”

Among London’s most audacious stunts was to promote his book, “Cruise of the Snark.” He and Charmian set sail on the South Seas with crew members who had never sailed before. It resulted in some memorable writing and boosted his star. But London contracted yaws, a hideous tropical infection, along the way, and scholars believe his self-treatment with a mercury-based ointment led to the kidney problems that contributed to his death.

That London was even born is a sort of miracle. The San Francisco Chronicle reported in June 1875 that a pregnant Flora Wellman tried to shoot herself after astrologer William Chaney, with whom she was living, disavowed the baby and tried to force Wellman to have an abortion. She gave birth to Jack six months later. Wellman married Civil War veteran John London when Jack was an infant and gave him her new husband’s name. London was a young man when he discovered that Chaney was his biological father and sought him out, only to be rejected again.

The facts of his life provide endless fodder for researchers and enthusiasts, who comb over writings that were often a mixture of truth and fiction. “Martin Eden” and “John Barleycorn,” an anti-alcohol tract exploited by Prohibitionists, were semi-autobiographical. London had periods on the wagon but he never gave up the drink for good.

“He’s a very complicated person. He’s got a lot of layers to him. I take him not always at his word,” said Tarnel Abbott, 62, London’s great-granddaughter. A social activist in Richmond, her father, Bohemian longshoreman Bart Abbott, was the only son of Joan London. The eldest of Jack’s two daughters, Joan was a radical in her own right who wrote about the plight of farm workers, fought for labor and aligned herself with Trotsky, activities that brought her under the scrutiny of the FBI. Joan had a complicated relationship with her father, stuck in the middle between two warring parents. Her mother, Bess, embittered that London left her for Charmian, kept her daughters away from Beauty Ranch.

But parsing fact from fiction misses the broader message, Abbott said. “There are things he has said or written that have meaning for me, that make me feel like I do try to carry on the way he might approve.”

Of London’s seven great-grandchildren

Abbott has emerged as the most outspoken keeper of the London legacy, and last summer presented an adaption of London’s “The Iron Heel” with music and giant puppets at the state park. Older sister Chaney Delaire — named for her great-grandfather’s absent father — lives in a modest house in Santa Rosa and worked 15 years in planning and community development for the nonprofit Burbank Housing. If there is any common thread through the generations, she said, it’s a deep appreciation of “the earth, the land and how important it is.”

But it fell to the offspring of London’s stepsister, Eliza, to steward the land London declared the most beautiful in California. When Charmian died, she left Beauty Ranch to Irving Shepard, Eliza’s only son. He tried to make a go of it as a guest ranch and dairy farm, but when Irving’s children, Milo, Jill and Joy, inherited the property, it came with a $1 million tax debt. Milo, who died in 2010, adapted by planting wine grapes and selling all but 160 acres of Beauty Ranch to the state in 1979.

His son, Brian Shepard, and Shepard’s cousin, Steve Shaffer, oversee the Jack London vineyards for a family trust. The Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Zinfandel and Syrah grapes have been sold exclusively to Kenwood Vineyards for 40 years. Brian’s brother, Neil, is the owner and driver of the Jack London Ranch Clydesdales and lives on the ranch, as does Shaffer.

They are committed to the same ethos of sustainability set by their great-uncle 100 years ago. Inspired by the farming practices he saw in the Far East, where farmers managed to keep land productive for centuries, London became an agricultural innovator. He terraced the land to protect the topsoil from washing down the mountain in rainstorms. He made his own compost, running a cable car from his mare barn to a manure pit outfitted with a concrete floor to keep in the nutrients. He tilled by horse, not tractor.

“I just came to wonder at how London landed here, on this truly great piece of property. The soils are really deep and varied,” said Brian Shepard, a laconic, 6-foot-4 man with the weathered hands of a farmer. “I appreciate the foresight, the good luck, whatever, that London realized this was a special place.”

“I’m blessed,” added Shaffer, almost sheepishly. “I didn’t do anything to deserve any of this. I just want to do my best to preserve it.”

London is experiencing a bit of revival, with a new generation of scholars examining his life and his work, shining a light on a writer who has not always been taken seriously. Readers may overlook London, some say, because they miss the underlying layers of what appear to be simple adventure stories. But that was a good measure of his genius: He was able to write stories that were page-turners and also had complexity for those who read deeper. Sonoma Valley educators are trying to engage young readers in Jack London, whose legend is still alive in the Valley of the Moon.

“Students are often surprised he had such modern ideas for being a guy who was ‘back in the day,’” said Alison Manchester, an English teacher atdren, Abbott has emerged as the most outspoken keeper of the London legacy, and last summer presented an adaption of London’s “The Iron Heel” with music and giant puppets at the state park. Older sister Chaney Delaire — named for her great-grandfather’s absent father — lives in a modest house in Santa Rosa and worked 15 years in planning and community development for the nonprofit Burbank Housing. If there is any common thread through the generations, she said, it’s a deep appreciation of “the earth, the land and how important it is.”

But it fell to the offspring of London’s stepsister, Eliza, to steward the land London declared the most beautiful in Sonoma Valley High School and a board member of the Jack London Foundation, which sponsors an annual writing contest that draws submissions from young authors from around the world.

“I would call him America’s storyteller,” said Jay Williams, who is at work on the second of a three-volume biography of London while on break from his work at the Huntington Library in San Marino (where most of London’s papers are stored). “That was how he was regarded in his time. We’ve lost that sense of Jack because we’ve been pigeon-holing him as a socialist or a traveler or an adventurer. When you look at him as a storyteller, it encompasses everything he did and that ultimately will be his legacy.”

The post The Times of Jack London appeared first on Sonoma Magazine.

]]>